Features

Crop Protection

Vegetables

How to know when your weevil is evil

A guide to distinguishing the pepper weevil from its doppelgangers.

June 1, 2020 By Cara McCreary and Dr. Rose Labbé

Figure 1. Pepper weevil caught on a yellow sticky card. PHOTO Credit: © Queen’s Printer for Ontario, 2020

Figure 1. Pepper weevil caught on a yellow sticky card. PHOTO Credit: © Queen’s Printer for Ontario, 2020

The pepper weevil, Anthonomus eugenii, is an economically damaging pest that can be found throughout all major pepper growing regions in North America. This pest can catch producers off-guard. Reproducing at exponential rates, it is incredibly laborious to manage and causes significant yield loss.

Management options are limited with few insecticides currently registered in Canada. Recent work has identified effective reduced-risk and biorational products to support new registrations and label expansions. However, available insecticides have limited efficacy largely due to the concealed immature life-stages, which develop inside the buds and pepper fruit, that go practically unscathed following an insecticide application. For best results, it is critical to detect pepper weevil early in the initial infestation period, then respond promptly with diligent scouting, removal of infested fruit and buds, and use insecticides when necessary. One of the most reliable tools to assist in early detection are pheromone baited traps. These traps include large yellow sticky cards and lures containing compounds found in naturally occurring aggregation pheromones. These aggregation pheromones are released by adult male pepper weevils, telling both male and female pepper weevils “this is where the party’s at – there’s food, there’s mates, come on over”.

One challenge encountered when monitoring these traps is that other equally small weevil species are often observed, and sometimes well before any pepper weevils ever appear. The conundrum, then, is that failure to properly identify and promptly respond to the presence of pepper weevil could rapidly lead to a difficult-to-manage pepper weevil population. In contrast, misidentifying a non-pepper weevil as one, could lead producers to spend more time and money on a higher-than-normal rate of crop scouting, infested fruit removal, and the unnecessary application of insecticides. For these reasons, the accurate identification of weevil species is essential to making informed and timely pest management decisions.

It can’t be that hard…

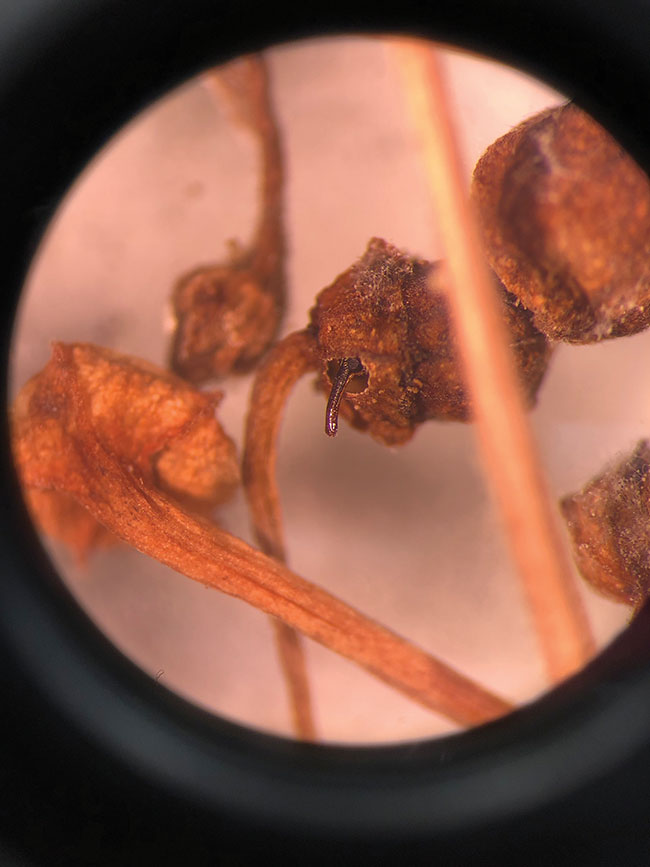

Figure 2. Snout of a pepper weevil emerging from an aborted pepper bud. Photo credit: AAFC, 2020

To give you an idea of the diversity of weevils in Ontario and Canada, we look to the 2013 Checklist of Beetles (Coleoptera) of Canada and Alaska (Bousquet et al., 2013). According to this source, there are currently 960 described species within the superfamily Curculionoidea (a.k.a weevils) in Canada; 480 of which are found in Ontario. Within that superfamily are the more relevant members of the family Curculionidae (a.k.a true weevils or snout beetles) of which there are 823 described species in Canada; 400 of which are found in Ontario. This family includes 37 weevil species belonging to the genus Anthonomus in Canada; 17 of which are found in Ontario. Some of these species not only closely resemble the pepper weevil, but may also respond to the same pheromones in baited traps designed to attract pepper weevil. However, in a greenhouse pepper crop, there is only one species that we really care about: the pepper weevil, Anthonomus eugenii. Because there are many similar morphological features among weevil species in general, it can be quite challenging to know just which species is stuck to your sticky trap. Essentially, we are expecting you to pick a needle out of a haystack. No big deal, right? So, how do we differentiate between pepper weevil and the hundreds of other weevil species in Ontario?

There must be a way to make this easier…

There is a way to make this easier. The first step is to determine which weevil species are most commonly observed on pepper weevil pheromone baited traps in a specific geographic location. Secondly, of those known species, we should determine which are most difficult to distinguish from the pepper weevil. Lastly, we need to determine which features to focus our attention on in order to tell them apart.

To answer these questions, the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA) and Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) initiated a collaborative effort aimed at identifying the numerous other weevil species found on pepper weevil pheromone baited traps in southwestern Ontario. This ongoing work is focused on distinguishing close relatives of the pepper weevil, and other morphologically similar weevil species to better assist IPM specialists, scouts and producers in confidently identifying the evil weevil with ease. Since 2016, thousands of weevils have been collected from traps, catalogued and their prevalence and seasonal occurrence recorded. With this information, we can help narrow down the list of suspects.

A weevil detective’s tools

To begin your detective work, it’s important to have the right tools in order to see body shapes, textures and other tiny features to help distinguish weevil species from one another. Most weevil features can be observed with a 10X hand lens or low magnification microscope. These days, digital USB microscopes or mobile phone attachments are relatively cost effective and can make it easier to take and share quality pictures of your specimens. As a bonus, this can also help build an image reference library useful for ongoing pest identification and management. Once you are set up with a suitable device, it’s then important to get familiar with morphological terminology typically used to describe insect body parts (i.e. Do you know what a femur is?). Doing so will help you work though the feature lists of described weevil species, and enable you to access a huge array of online resources that can be used to rapidly compare your specimen to other relatives. Together, these tools combined with this guide should make identification of weevils as comprehensive as possible.

Uncovering the details of the pepper weevil

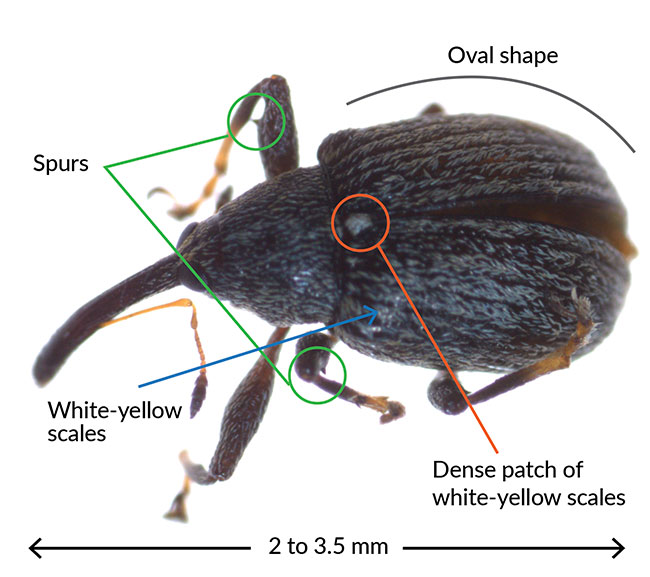

FIGURE 3.

Anthonomus eugenii – Pepper weevil: Note the spurs under each of the six femora, white-yellow scales on body and wing covers, oval-shaped body with strongly arched back, and a small dense patch of white-yellow scales at the top of the wing covers. Photo credit: © Queen’s Printer for Ontario, 2020

First, there are certain morphological features that can be particularly helpful for ruling out many beetle species and distinguishing between the more relevant weevils. For starters, we can begin by looking for the Muppet character, Gonzo. In other words, does your specimen have a snout? Pepper weevil and its close relatives all have a snout, which is basically the nose of the weevil and looks a bit like an elephant’s trunk. (Note: there are some weevils that don’t have snouts). Other distinguishing features specific to the pepper weevil, Anthonomus eugenii include (Fig. 3):

- 2-3.5 mm length (head to tip of abdomen)

- Black-brown-mahogany coloured body (quite variable)

- White-yellow scales (look like thick hairs) on the body and elytra (wing covers); scales are in slight disarray (picture Albert Einstein) relative to some other species

- Very small, but dense, patch of scales in the centre top dorsal (i.e. their back) section of the weevil located between the two wing covers – this section of the body is called the scutellum (picture a small, whitish circular patch at the base of the neck where the wing covers meet)

- Oval-shaped body

- Strongly arched back (very notable and a common trait of the genus Anthonomus)

- Spurs on the underside of all 6 femora (picture a thorn on a rose stem protruding from the back of its thigh)

Despite these key features of the pepper weevil, many other weevils have similar-looking traits and it can be tough to tell some of them apart. Let’s look at features that can help us rule out these other species.

The innocent weevils (in a pepper crop)

FIGURE 4.

Cosmobaris scolopacea – Beet petiole borer Photo credit: Tom Murray, BugGuide

Among the specimens we captured on pheromone baited traps, some looked wildly different from the pepper weevil, such as the beet petiole borer, Cosmobaris scolopacea (Fig. 4) or the green immigrant leaf weevil (Polydrusus formosus) (Fig. 5). Others have a striking resemblance in size and features. One further confounding factor to identification is that sometimes the glue from sticky traps can change a specimen’s appearance to the point where easily distinguished features are less obvious or entirely hidden. Therefore, it’s important to look closely at the series of features that can help rule out other weevil species as culprits. Specifically, look at size, colour, density of scales, the presence of spurs and perhaps most notably, the body shape. Ask yourself, “What is similar to the description of a pepper weevil and what is different?”

FIGURE 5.

Polydrusus formosus – Green immigrant leaf weevil Photo credit: CHRIS JOLL, BugGuide

There are a few other key weevil genera that keep popping up among our collected specimens including other Anthonomus, Ceutorhynchus, and Tychius species. Some of these other species frequently appear on traps in spring and early summer as they emerge from overwintering sites and their suitable hosts are available, whereas the pepper weevil tends to be more prevalent during mid-to-late summer. However, it is possible to observe the pepper weevil at any point throughout the growing season. Below are some of the distinguishing features of commonly collected weevil species found on pepper weevil pheromone baited traps:

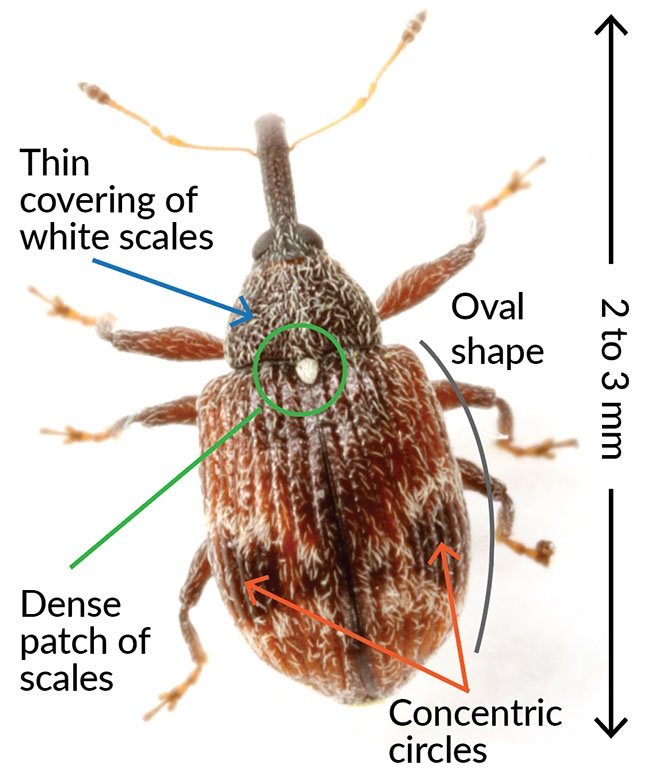

FIGURE 6.

Anthonomus signatus – Strawberry clipper weevil: Note the thin covering of white scales, a small, dense patch of scales at top of wing covers, and large concentric circles on wing covers with white scales surrounding a black centre. Photo credit: Mike Quinn, TexEnto.net

Anthonomus signatus – Strawberry clipper weevil or strawberry bud weevil (Fig. 6)

- 2-3 mm length (similar)

- Small, dense patch of white scales in the centre top dorsal section between the two wing covers (i.e. the scutellum) (similar)

- Oval body shape (similar)

- Thin covering of scales (slightly thinner than the pepper weevil)

- One large concentric circle on each wing cover, in which white scales surround a large nearly black centre – the rest of the weevil body varies in shades of reddish-brown and black (this is the feature that will most likely set it apart from the pepper weevil)

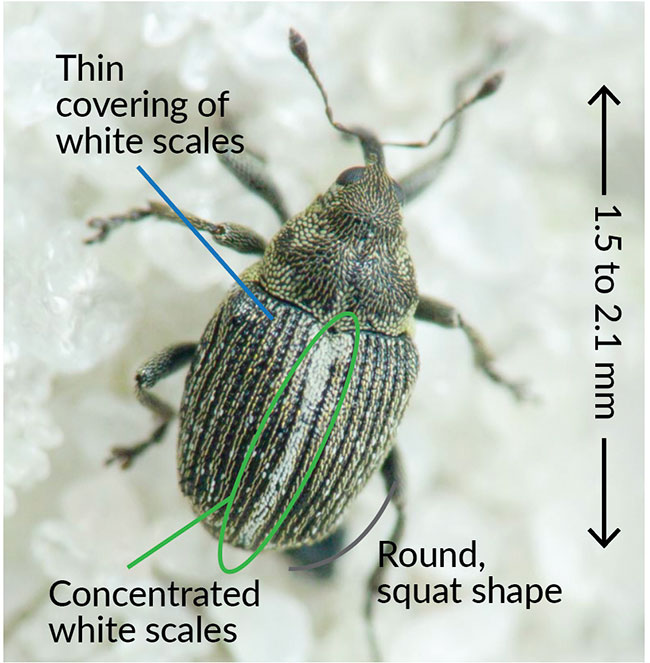

FIGURE 7.

Ceutorhynchus typhae: Note the concentrated white scales at the top of the wing covers and down the centerline, a thin covering of white scales on the body, and round, squat body shape. Photo credit: Boris Loboda. UkrBIN. 2020

Ceutorhynchus typhae (Fig. 7)

- 1.5-2.1 mm length (smaller)

- Concentrated white scales at top of wing covers and down centerline (usually a clear “white skunk stripe”)

- Thin covering of white scales on body (similar)

- Round, squat body shape (different)

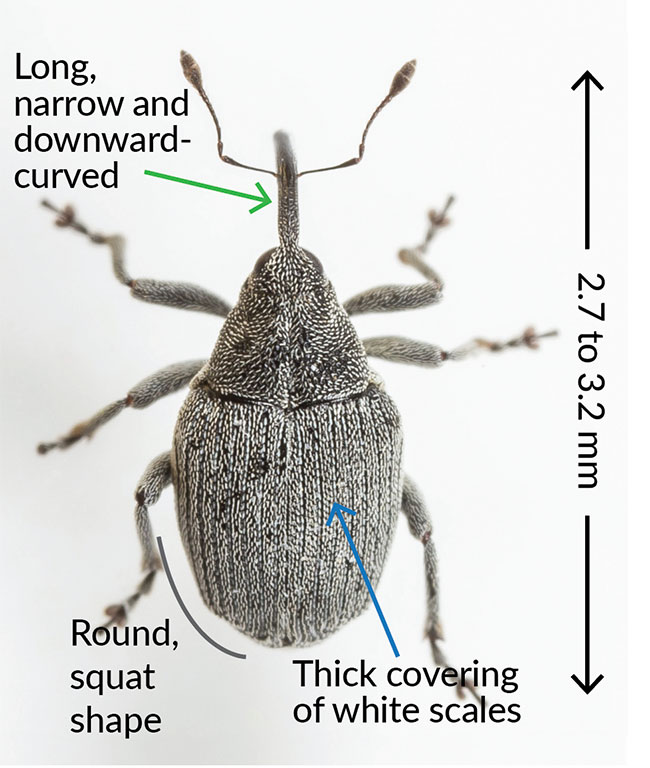

FIGURE 8.

Ceutorhynchus rapae – Cabbage weevil:

Note the snout is long, narrow and downward-curved, body appears grey due to a thick covering of white scales on the black body, and a round, squat body shape. Both photos: John Rosenfeld, BugGuide

Ceutorhynchus rapae – Cabbage weevil (Fig. 8)

- 2.7-3.2 mm length (similar)

- Body appears grey due to thick covering of white scales on black body (different – the grey is very noticeable when placed side-by-side with the pepper weevil, but may not be when observed on its own)

- Snout is long, narrow and downward-curved (somewhat different)

- Round, squat body shape (different)

In addition, Ceutorhynchus erysimi is also occasionally collected (photo not shown). While it has some similar characteristics to the above-mentioned Ceutorhynchus species, including a similar body shape and smaller size of approximately 1.8 to 2.7 mm length, C. erysimi can be distinguished by its black shiny body with metallic blue-green wing covers, and the virtual absence of scales.

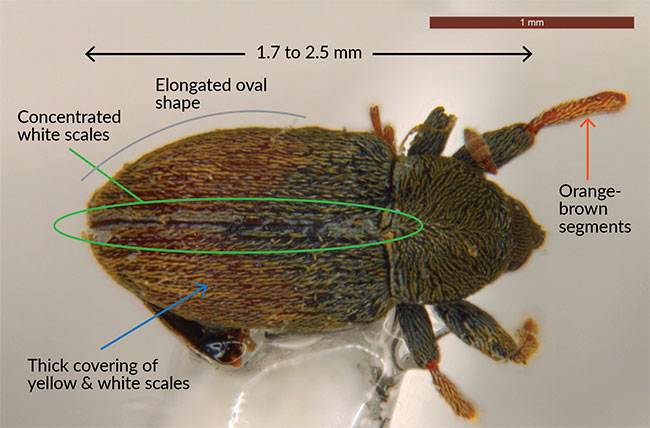

FIGURE 9.

Tychius meliloti – Sweet clover weevil: Note the orange-brown lower leg segments, a thick covering of yellow and white scales, concentrated white scales at the top of the wing covers and down the centerline, plus an elongated oval body shape. Photo credit: Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Harrow Research and Development Centre, 2020

Tychius meliloti – Sweet clover weevil (Fig. 9)

- 1.7-2.5 mm length (smaller)

- Brown body (the distinct amber-brown colour may be a dead giveaway)

- Concentrated white scales at the top of wing covers and down centerline (usually a clear “white skunk stripe”)

- Thick covering of yellow and white scales (different)

- Elongated oval body shape (different)

- Lower leg segments are orange-brown (somewhat different)

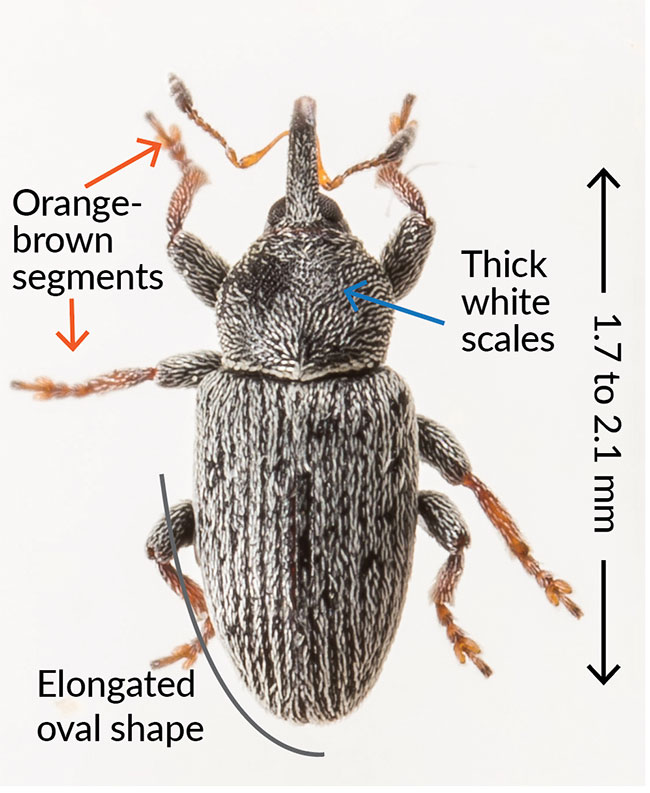

FIGURE 10.

Tychius picirostris – Clover seed weevil:

Note the orange-brown lower leg segments, thick white scales on the body, and an elongated oval body shape. Both photos: John Rosenfeld, BugGuide

Tychius picirostris – Clover seed weevil (Fig. 10)

- 1.7-2.1 mm length (smaller)

- Body is dark greenish-brown to black (somewhat different)

- Thick white scales on body (somewhat different)

- Elongated oval body shape (different)

- Lower leg segments are orange-brown (somewhat different)

FIGURE 11.

Left: Pepper weevil. Right: Baridine specimen. Both Photos: Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Harrow Research and Development Centre, 2020

Aside from these common weevil species often found on pepper weevil pheromone baited traps, there are other weevil species in Ontario belonging to subfamily Baridinae (Fig. 11) that also share a considerable resemblance to the pepper weevil. Members of this group are incredibly difficult to identify at the species level. However, there are some key features that can be useful for identifying members of this subfamily. Males have obvious prosternal spines protruding from their heads (picture horns coming from the underside of their neck)

FIGURE 12.

Prosternal spines on baridine specimen. Both Photos: Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Harrow Research and Development Centre, 2020

(Fig. 12) – these are used in male-to-male combat. At first glance however, the females can look remarkably like the pepper weevil. Perhaps the most important difference is the body shape – the pepper weevil has an arched back while the baridine weevils do not.

It is noteworthy that pepper weevil’s doppelgangers may be pests in other crops, but not in peppers. Ultimately, the basic information provided here can be a useful first resource for quickly weeding out the weevils that aren’t of interest to pepper producers and identifying the weevils that likely are. Although we would urge you to look for these details when first observing and distinguishing specimens yourself, when in doubt or when a specimen strongly resembles the description of a pepper weevil, it is important to reach out to your trusted IPM specialist or entomologist for confirmation. Either way, if you are a pepper producer and find a weevil on one of your traps, don’t panic until you know that your weevil is in fact evil.

Reference

- Bousquet, Y., P. Bouchard, A. E. Davies, and D. S. Sikes. 2013. Data associated with Checklist of beetles (Coleoptera) of Canada and Alaska. Second edition. Data Paper. ZooKeys. http://dx.doi.org/10.5886/998dbs2a

Cara McCreary, MSc, is the greenhouse vegetable IPM specialist at the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs. Rose Labbé, PhD, is the greenhouse entomologist at Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada. Questions? Email Cara at cara.mccreary@ontario.ca.

Print this page