Features

Crop Culture

Flowers

Growing perennials from seed

The differences between vegetative and seed-propagated perennials, and why moisture is key to good germination.

November 17, 2020 By Chris Fifo

Breeding new varieties from seed can take more than a decade, such as this new Echinacea Artisan Soft Orange.

Breeding new varieties from seed can take more than a decade, such as this new Echinacea Artisan Soft Orange. As a class, the interest in and sales of perennials have been skyrocketing. And why not? Perennials are so much more exciting than annuals! (Granted, that’s just my opinion. But a new series of Aquilegia or a new colour of Petunia? No brainer.)

Breeding has come a long way in perennials. And while the competition among breeders can be intense, this leads to superior-performing perennials that benefit growers, retailers, landscapers and gardeners. Many of the newest introductions have come from the vegetative side. Mainly because this is a much faster process. But there have been, and continue to be, amazing introductions in seed perennials.

What are the primary differences between vegetative and seed-propagated perennials, and when would I choose to go with the seed option?

I’ll answer these questions for you and will then offer a few pointers to one of the primary pain points for those considering seed: germination.

Choices

Seed perennials won’t offer you as many choices in species, colours or flower forms as their vegetative counterparts simply because of genetics.

Many vegetative varieties are developed from a single plant that has expressed one or more recessive gene traits, where the combination of all those attributes is collectively known as a “phenotype.” This plant with desirable attributes is then cloned to become a new variety. This process can happen relatively fast, which is why you have hundreds of vegetative Echinacea and Heuchera to choose from.

A new variety from seed can take more than a decade to develop. Controlled inbreeding is first performed to eliminate recessive traits and have dominant, but different, desirable attributes consistently expressed in both parent lines. Flowers are then cross-pollinated by a controlled process, and the resulting seed are known as F1 hybrids. When a new series is developed from this process, it is exceptionally exciting!

Seed perennials are an attractive option for growers for several reasons:

Price point: Seed is almost always a more cost-effective option. This allows growers more flexibility for container sizes and marketing options than some vegetative counterparts, which may have to go into larger containers or branded programs to achieve comparable margins.

“Seed in the bag beats tissue culture in the lab”: Most new Echinacea are propagated by tissue culture in a laboratory. This is a slow process and inventory can sometimes be limited. Meanwhile, seed is harvested by the hundreds of thousands and, unlike tissue culture, can be stored until it is needed.

Hardiness: Though this cannot be generalized, and maybe not even scientifically proven, there has been a general perception that some of the latest and greatest vegetative perennial varieties are losing some of their hardiness compared to the original seed varieties.

First-year flowering: There are still genera that require vernalization for full flowering. Breeding advancements are reducing or eliminating this need for some. However, first-year flowering makes plants much easier to grow and accurately schedule seed perennials for flowering.

Uniformity: Because F1 hybrid seeds are produced by controlled pollination between the two parental lines, the resulting hybrids are an immense improvement over standard open-pollinated (OP) varieties, offering greater uniformity and vigour in growth habit and flowering.

Enjoyment: Growing perennials from seed is fun!

Innovations

Okay, that last point was purely subjective from my experience. I understand not everybody shares that feeling. Perennials have traditionally been perceived as difficult to germinate, at least compared to annuals. This can make growers shy away from seed propagation in favour of rooting cuttings. However, this does not have to be the case. Anyone can be successful at germinating and growing perennials from seed.

Not only have there been advancements in breeding and seed production, but seed processing and treatments have also come a long way. This makes it easier for growers to sow and grow seed perennials. Below are some treatments being advanced by seed companies to help growers better succeed with perennials:

- Cleaned and de-tailed seed that doesn’t bunch together;

- Coated seed will run through a seeder more easily;

- Fungicide coating for crops like Lupine can minimize disease issues;

- Pelleted and multi-pelleted seeds for crops like Campanula that are very small and perform best with several seeds per cell and;

- Proprietary treatments to enhance germination and vigour.

In the end, it is up to the growers for success, but here are a few guidelines to help you along the way.

From my experience, perennials are not too picky on temperature – anywhere from 17ºC to 24ºC seems to work fine. The biggest difference is the rate of germination. Likewise, I have not experienced differences in light versus no light for germinating commercial varieties.

Another misconception for some perennial seed is that they need to be cold stratified to overcome dormancy issues. This is not the case these days. Those “proprietary treatments” have solved that problem.

The primary factor affecting germination of perennials is moisture. It is that simple, and it can be that challenging. If you’re having difficulties germinating perennial seeds, evaluate your moisture.

I trust everyone is familiar with the 1 to 5 media moisture scale: 5 being saturated, 1 being completely dry, and 3 just turning from dark to light coloured. Most issues occur from growers keeping their seeds at a 5 for germination. Even those crops that like to germinate wet will prefer a 4 to 4.5 for moisture.

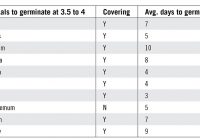

How is a grower to know? First, do a little homework. There is information available through resources provided by seed breeders, such as PanAmerican Seed. If you can’t find information there – such as if you’re germinating older genetics or native plants – look at the seed itself and use your instincts.

Is it a smaller, hard seed like a Dianthus or Salvia? Then it probably needs to be kept more wet and does not need vermiculite or media covering on the seed.

Is it a larger seed? The size of a BB gun or larger like a Centaurea or Lupine? Then maybe it needs covering, but don’t bury it more than the diameter of the seed.

Is it a larger, soft seed like a Delphinium or Echinacea? Then it probably prefers to have a little covering and be germinated on the dry side, around a 3.5 or 4.

Germination is easily done on the bench for the wet germinators. Managing moisture for the drier germinators is more challenging. The use of a germination chamber can help keep the humidity around 85 to 90 per cent. That way, if a plug tray goes into the chamber at a 4.5, it will gradually dry to a 3.5 by Day 3 or 4. Perfect. By this time, the seed has absorbed all the moisture it needs to germinate. Using a mist nozzle after this to avoid desiccation is all you need to maintain the perfect moisture level and have success germinating perennial seeds.

Chris Fifo has more than 30 years’ experience as a technical services advisor. His expertise lies in best practices for perennial production and is a product representative for both Kieft Seed and Darwin Perennials. He can be reached at cfifo@ballhort.com.

Print this page