Features

Flowers

Water and irrigation

A plant-centered approach to watering

Does dry soil promote root growth? Research and greenhouse experience would disagree.

March 30, 2020 By Albert Grimm

On a sunny day in late May, it may take more than 15 irrigation cycles per day, with 1-2 ounces of water per cycle to maintain fully mature hanging baskets at moisture level 3. Tight water control allows us to create sturdy, drought-resistant plants with excellent garden center and consumer shelf-life. All photos: A. Grimm

On a sunny day in late May, it may take more than 15 irrigation cycles per day, with 1-2 ounces of water per cycle to maintain fully mature hanging baskets at moisture level 3. Tight water control allows us to create sturdy, drought-resistant plants with excellent garden center and consumer shelf-life. All photos: A. Grimm Grower knowledge is permeated by greenhouse lore that is enduring but not always accurate. One of these myths claims that dry soil promotes root growth, because roots are forced to ‘search for water’. Consequently, growers dry their crops into mild water stress to aid the development of root systems. The problem is that practically all plants disagree. We know that moisture stress and dry/wet cycling produces less root mass and branching, not more. This is confirmed by close-to-home research at the University of Guelph.

Plants develop roots where they find the best conditions for water and nutrient uptake. Root hairs, the active parts of most roots, work best when they are continuously covered by a thin film of liquid water with a comparatively large air-filled space beyond the water layer. In other words, roots place themselves exactly at the boundary of a wet surface and a body of air. Availability of water stimulates root hair development, and the air is necessary for oxygen supply, because oxygen must continuously dissolve into the water film covering the root hairs. Water moves into the cells and brings along necessary oxygen. Root hairs suffocate if they are not surrounded by air-filled spaces and if no oxygen dissolves in the water that enters the plant. Substrate that is too wet or does not hold air spaces creates thin, rapidly elongating roots without any hairs. If the substrate is too dry, adequate root hairs will not develop and root development slows down. So, roots do not search for water, but for conditions that are ideal for root hairs.

How can we measure whether plants get the conditions that they need?

The plant perspective of happy roots allows us to use purpose when we apply water to a crop. However, before we can do so, we need a method to measure soil moisture that allows us to compare between different crops and different seasons.

Soil colour, experience-based judgement, and the often-clichéd feeling in one’s gut merely represent a grower’s idiosyncratic perspective of how wet or dry any substrate should be. Neither of these provide us with any plant perspective. We need a reliable measure of how much water is available in any given substrate before we can assess the effect on roots. For this purpose, we have developed a 5-step moisture scale for peat-based container substrates, where level 1 is dry and level 5 is wet. This is how we define these moisture levels:

Moisture Level 5: The substrate is saturated with water. We can easily squeeze an abundance of water out of the substrate. When a small amount is placed on a sheet of paper or cardboard, it leaves clearly visible droplets or a wet spot, even when no pressure is applied. Plant Experience: Roots do not find enough water-to-air boundaries, because all capillaries in the substrate are flooded.

Moisture Level 4: The substrate is at moisture capacity, but it does not contain any freely draining water. The substrate looks wet, and we can squeeze out some droplets of water, but it does not leave any wet spots when it is placed on a sheet of cardboard. Plant Experience: Roots find plenty of water-to-air boundaries, because the capillaries are filled with air. Water uptake is unrestricted. As we increase moisture beyond level 4, the water-to-air boundaries gradually disappear because the capillaries begin to flood.

Moisture Level 3: The substrate changes colour from dark/black to light/tan and contains visibly less moisture. The substrate still feels moist to the touch, but we can no longer squeeze out water unless we use extraordinary effort. Plant Experience: Roots find plenty of water-to-air boundaries. Water uptake is slightly restricted, and the root system is expanding with healthy root hairs. Practically all ornamental crops develop optimal root systems if substrate moisture is maintained at level 3.

Moisture Level 2: The substrate is very light/tan in colour and does not contain any visible moisture. The substrate feels dry to the touch. The crop is under discernible water stress, but it does not wilt. Plant Experience: The root system is working at full capacity to extract water from the substrate. This is about as dry as we will take most crops without fear of damaging them permanently. If we decrease moisture beyond level 2, the residual water films disappear.

Moisture Level 1: The substrate is completely dehydrated. It loses its elasticity, visibly shrinks, and often separates from the container. The crop is under severe water stress and loses turgor. Plant Experience: Many sensitive crops are permanently damaged by these conditions.

How do plants respond if we change the moisture content of the substrate?

Moisture Level 3 is the sweet spot. Almost all containerized crops would be perfectly happy if we could maintain this level all the time. It offers a perfect balance of moisture to air in the substrate, and plants can comfortably regulate water uptake to balance turgor pressure.

If we increase moisture to level 4, water-to-air boundaries and oxygen supply will remain intact, but water is available for uptake with almost no resistance. That’s OK if the plants can evaporate the water at the same rate as roots pump it into the system. However, when the greenhouse climate changes rapidly, e.g. at nightfall after a sunny day, the roots may not be able to reduce uptake quickly enough, and as a result of increased turgor pressure, cells begin to stretch, internodes elongate, and foliage expands. For some crops this may be advantageous, but most ornamental growers are in the business of selling compact canopies underneath abundant flowers and stretch is not desirable.

If we reduce moisture from the sweet spot towards moisture level 2, we make it harder for the plant to take up water and nutrients. This reduces stretch and canopy expansion, but it also reduces root growth and photosynthesis, particularly during warm, bright weather when plants need a constant supply of water for evaporation.

How can we use all this knowledge to manage plant health and habit?

Growers should not just water plants. Growers should operate root systems. We need clear objectives before we can make purposeful decisions about watering plants. Do we want to optimize biomass production, or are we concerned about too much canopy? Can we trade off stress tolerance for optimal photosynthesis, or do we need tough plants that survive for weeks in a hot, dry garden center without being watered regularly?

Our target moisture level should match our objective. Moisture level 3 is adequate for most crops, but we can increase drought tolerance if we are to operate closer to level 2. If we have a greenhouse optimized for biomass production, we may want to aim for moisture level 4 to maximize potential water uptake.

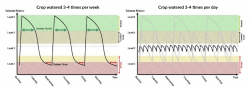

The practical challenge is to develop irrigation methods that achieve our target moisture level with only minimal fluctuation. For uniform substrate moisture, we must water as frequently as our irrigation system allows with as small a volume per irrigation as possible. Infrequent watering requires larger volumes of water per irrigation and results in larger fluctuations of substrate moisture between cycles. If we simply wait until the crop is dry before we water thoroughly, we get maximum moisture fluctuation and are no longer able to manage the root system.

Learn how to control grower panic!

Grower panic is the most common cause of water-related crop damage. Let’s imagine that you arrive at the greenhouse and one of your crops is wilting. You realize that you will be in big trouble if anybody else sees such a sad picture. You get grower panic, and you rush to get water to these wilted plants as quickly and as thoroughly as you can manage. A few days later, the roots are dead, and the quality of this crop is toast. Such damage would not have been caused by the wilt, but by the water.

Severe water stress followed by excessively wet conditions is deeply problematic for plants. The tender root hairs of moisture stressed plants are using enormous force to pull out the last drops of water film from dry soil. If we suddenly inundate the substrate and the roots with an abundance of water, these root hairs do not have enough time to shut off their water pumps. Water rushes into the cells, and the resulting internal pressure bursts their tender membranes. The root hairs explode. The resulting wounds allow diseases like Pythium to establish, and this is the key trigger for water molds. Even if the roots survive unscathed, the sudden change in turgor pressure can cause a variety of other undesired physiological symptoms on the plants.

The proper way to re-hydrate any severely dry or wilted crop is slowly. Initially, give the plants no more than a few drops of water, preferably over the foliage to reduce stress. After 20 minutes, give them a few drops more, and let the roots know that water is coming. Give the roots time to adjust, and then re-hydrate the soil very slowly by watering repeatedly over an 8-10 hour period. Doing so is more effective at preventing root rot than a fungicide drench.

Albert Grimm is head grower at Jeffery’s Greenhouses in St. Catharines, Ont. He can be reached at albertg@jefferysgreenhouses.com

Print this page