The iconic image of the rural English countryside is that of a quaint

cottage with a thatched roof and ivy-covered walls. Both circumstances

and technology have changed dramatically since those cottages were

built centuries ago, but that image of green roofs and living walls is

making a resurgence in urban North America, and on a much grander scale.

The iconic image of the rural English countryside is that of a quaint cottage with a thatched roof and ivy-covered walls. Both circumstances and technology have changed dramatically since those cottages were built centuries ago, but that image of green roofs and living walls is making a resurgence in urban North America, and on a much grander scale.

|

| Reece Rehn of Holland Landscapers (second from the left), Andrea Martinello GRP, and Rod Nataros, Haley Argen and Ange Desaulniers from N.A.T.S. PHOTOS COURTESY N.A.T.S. NURSERY LTD. Advertisement

|

Leading the way is N.A.T.S. Nursery of Langley, British Columbia, a 21-year-old nursery that has been growing plants for green roofs and living walls for the past eight years.

It’s become a major focus for the company, says owner Rod Nataros, calling them “another opportunity to push plants.”

VANCOUVER HOME TO THE LARGEST NON-INDUSTRIAL GREEN ROOF INSTALLATION IN NORTH AMERICA

N.A.T.S. recently celebrated its biggest success with the opening of the striking new Vancouver Trade & Convention Centre. The Centre features a green roof spanning over six acres, making it the largest green roof in Canada and the largest non-industrial installation in North America.

|

|

| The roof in May 2008 PHOTOS COURTESY N.A.T.S. NURSERY LTD. |

The roof features 400,000 indigenous plants and grasses. It has over 5,000 cubic metres of growing medium weighing just shy of five million kilograms, consisting of lava rock, topsoil and gravel (about six inches deep). The topsoil consists of dredged silt from the Fraser River. The drainage and water recovery systems collect and reuse rainwater as irrigation and utilize 43 kilometres of drip irrigation piping. No chemical fertilizers, pesticides or herbicides will be used. The roof will be mowed each fall, and the clippings will be composted into the roof soil.

It took Holland Landscaping nine months, spread over a year, to install the green roof on the Centre, complete with a row of beehives.

Before the project began, N.A.T.S. and landscape architect Bruce Hemskirk spent over three years researching which plants were best suited to simulate a “wild meadow” on the roof. They selected a mix of three fescues, four carexes, native sedum, wild beach strawberry and aster. All but one are considered native plants.

“I prefer to grow native plants whenever possible. It’s important for sustainability,” Nataros says.

ALPINE PLANTS ARE BEST BECAUSE THEY HANDLE WEATHER EXTREMES

“We trial a lot of plants we suspect will be good on green roofs,” notes N.A.T.S. plugs salesperson Holly Argen, saying many tend to be alpine plants “because they can take weather extremes better.”

N.A.T.S. is the Canadian supplier of the trademarked Live Roof invisible modular green roof systems. Live Roofs, which are primarily sedums, come in mats, allowing the contractors to simply “unroll” the plants, much as they would a roll of tarpaper.

|

|

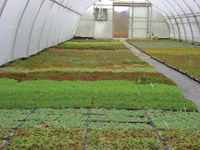

| The main propagation house with seeded Cornus canadensis. PHOTO COURTESY N.A.T.S. NURSERY LTD. |

While green roofs are more expensive than conventional roofs, they offer such benefits as storm water mitigation, energy conservation, better air quality, habitat creation and improved esthetic value. That resonates with urbanites who are becoming increasingly environmentally conscious, says Adam Weir of Paradise Cityscapes in Victoria. An N.A.T.S. client, Weir is a landscaper and contractor who has been installing green roofs in Victoria and the Gulf Islands for the past five years. “Urbanites want to be more sustainable,” he notes.

They are also a pleasure to work with, he says, calling it “easier than working on the ground because you start with a clean slate.”

GREEN ROOFS REQUIRE EXTRA SUPPORT

However, he admits green roofs can have their challenges.

“There are a lot of failures out there,” says Weir. First, roofs need the extra support of 2×6 rafters. “A standard 2×4 roof on 16-inch centres is not strong enough.”

Finding the right type and dosage of fertilizer can be another challenge. “We’re trying to make it as natural as possible but it’s still a manufactured product,” Weir points out.

There can also be pest issues. Weir recalls one of his roofs was in the path of a rookery. “The crows came and plucked out all the sedum plugs.”

Nataros believes green roofs will increase exponentially as people become more familiar with them. It does not hurt that LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) standards provide extra ratings points to buildings that include a green roof and/or living wall.

Although not used on the Convention Centre green roof, one of the many plants N.A.T.S. grows, which Argen is particularly proud of, is a snow cinquefoil (Potentilla nivea). That’s because it’s one she discovered herself in the Yukon and is now proving quite popular.

SOME OF THEIR FAVOURITES WERE FOUND IN THE YUKON

“For many years, I lived in the Yukon and worked as a Yukon nursery grower in the summer, then came down to work at N.A.T.S. in the winter,” she explains. “When I came down, I would bring seeds with me which we then propagated at N.A.T.S.”

|

|

| An N.A.T.S. cold frame with sedums. Green roofs typically use a lot of sedum in their mixes. PHOTO COURTESY N.A.T.S. NURSERY LTD |

To do that, N.A.T.S. has a computer-controlled 13,000-square-foot propagation house. It is among 125,000 square feet of greenhouse space (10 heated houses and several more cold frames) on the 28.5-hectare nursery.

The snow cinquefoil is an example of the company’s attempt to grow all kinds of native plants, many used in remediation work. “We try to grow plants for specific areas,” Nataros says.

Arctostaphylos is an example. N.A.T.S. grows one variety for the wet B.C. coastal climate and another for use in the drier interior.

GROWING SITE-SPECIFIC PLANTS FOR SOME PROJECTS

Sometimes, the nursery can go to extreme lengths to grow site-specific plants. For example, they are currently working on a project in Inuvik. They began by collecting seeds from the site, bringing them down to the nursery to propagate and grow, then shipping them back to Inuvik in containers.

“The project will have plants as native as they can get,” Argen says.

Nataros said that approach can have its challenges. By the time the Inuvik

deal was signed, the plants had stopped producing seeds, so the project had to be delayed a year until new seeds were available.

N.A.T.S. grows several million plants each year, everything from plugs to big plants in 20-gallon pots. While it specializes in native plants, hardy ferns and ground covers, head grower Angela Anderson says they like to dabble in plants that may be more difficult to grow. Snow berries is one example, as they take two years of seed treatments before they can be propagated. Arbutus is another plant they are proud of.

“Arbutus is difficult to grow but we’ve figured it out,” Anderson says. ■

David Schmidt is a freelance writer and photographer in British Columbia.

Print this page