Features

Biocontrols

Inputs

Understanding Ervi: Tips for successful foxglove aphid control

Contrary to some previous reports, this parasitoid is more effective than you might think.

September 11, 2018 By Ashley Summerfield Dr. Michelangelo La Spina Dr. Sarah Jandricic and Dr. Rose Buitenhuis

The aphid parasitoid Aphidius ervi.

The aphid parasitoid Aphidius ervi. When we started our project to develop a more effective IPM strategy against foxglove aphids, one of the first questions we tried answering was “Why doesn’t Aphidius ervi provide good control?” Growers and IPM specialists have previously reported that this aphid parasitoid does not seem to be effective in controlling the relatively “new” aphid pest – foxglove aphid.

However, experiment after experiment in our lab (and subsequent trials at Cornell University) demonstrated that not only did A. ervi control foxglove aphids, it actually out-performed other biocontrol agents tested.

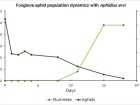

So if A. ervi is actually effective in controlling foxglove aphids, as demonstrated in our trials (see graph below), how did it manage to get such a bad reputation? And why did so many growers stop relying on this parasitoid and switch to pesticides only to control this aphid pest?

Following an in-depth study of the interaction between A. ervi and foxglove aphids, we realized that the measures of efficacy and release strategies being used weren’t a good fit for the parasitoid or pest.

Great Expectations

How well a pest is being controlled is the ultimate measure of how effective a natural enemy is. However, “good control” depends on the perception of the grower. What one grower might perceive as “good control” might be different for another one, depending on their expectations.

One thing that can drive the perception of “good” or “bad” control is the speed at which it takes place. Unfortunately, the effect of parasitism is not immediate as seen with predators or sprays, which begin to take effect straight away. For most parasitoids, it will take at least a week to see the effect, sometimes two, depending on the temperature of the greenhouse. In our greenhouse trials with A. ervi, true control (bringing aphid populations to nearly zero) wasn’t achieved until about the two-week point. For growers who have been using sprays to control aphids, getting accustomed to this delay in effect requires patience.

Another common measure of efficacy when using parasitoids is the number of mummies found. This gives an indication of the parasitism (or attack) rate. Papery brown aphid mummies begin to appear a week or two after releasing parasitoids. The number of mummies is a good indicator of pest control for parasitoids like Aphidius colemani (the primary parasitic wasp for melon and green peach aphid). But this doesn’t appear to be true for A. ervi.

Know Thy Enemy

Not all aphids behave the same way in response to an attack. The arrival of a parasitoid can trigger two different responses in the aphid colony. Some species (like green peach aphid) stay in the same place and many mummies are found where a colony used to be. Other aphids (especially foxglove aphid) try to run away, or even drop off the plant when in danger. This means that you may not find mummies on the leaves where you expect them to be.

So, which situation is better? Obviously, seeing dozens of mummies is much more reassuring to the grower than only finding one, but BOTH scenarios can lead to good control.

In our trials, we observed that when an A. ervi lands on a leaf, it can clear away all foxglove aphids within a few minutes (whether it parasitizes them all or not) due to the “defensive dropping” behaviour of this aphid species. Jumping ship (or leaf, in this case) might sound like a good defence strategy, but it comes with its own risks.

If the foxglove aphid was first parasitized before it escaped, mummies can end up almost anywhere (on the bench, or on plants a few metres away). If they weren’t parasitized, they still might die from getting trapped in water, injured in the fall, or end up on the floor (not a great place for an aphid). To survive, the aphid will have to expend energy to find its way back onto the plant. The time the aphid spends trying to find its way back is time it’s not spending feeding and reproducing. Scientists call these types of misadventures “non-consumptive effects”. Non-consumptive effects are known to also contribute to effective control (up to 50 per cent of biocontrol can be attributed to this). If the aphid does manage to get back to the crop, and parasitoids are still around, they will have an easier time parasitizing an aphid that is starved and weakened by its journey.

Set A. ervi up for success

Ultimately, we know from our research (including on-farm trials in flower crops in Quebec) that under the right conditions A. ervi can do a great job maintaining foxglove populations at low levels. So what can growers do to make sure they succeed?

- Release as soon as you find foxglove aphids. Our long-term greenhouse trials indicate that releasing A. ervi before the aphids arrive results in them giving up the search and leaving the greenhouse (or dying). (This is in contrast with strategies used for other aphid pests, e.g. A. colemani for green peach aphid control, where releasing the parasitoid preventatively seems to work better). On the other hand, if you wait too long to release them, the aphid population growth can exceed the parasitoids’ ability to control them.

- Release A. ervi weekly until aphid populations start to decline, then reduce to every two weeks.

- Use distribution boxes (available from most suppliers) when releasing. If you sprinkle the product, a lot of mummies can end up on the soil surface, bench, or floor, and can be ruined by conditions that are too wet.

- After emergence, parasitoid wasps appreciate a source of sugar. They can feed on honeydew once they locate aphid colonies, but we can give them a head start by dabbing a droplet of honey on the side of the distribution box for them to feed on as soon as they emerge. This will ensure they have plenty of energy to search for aphids, and can prolong their activity in the greenhouse.

Now that you understand this parasitoid better, don’t you think it’s time you gave Aphidius ervi a second chance?

Ashley Summerfield is a research technician in biological control; Michelangelo La Spina, PhD, is a former research associate, and Rose Buitenhuis, PhD, is the research scientist of biological control at Vineland Research and Innovation Centre. Sarah Jandricic, PhD, is the greenhouse floriculture IPM specialist with the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs.

Print this page