Features

Structures & Equipment

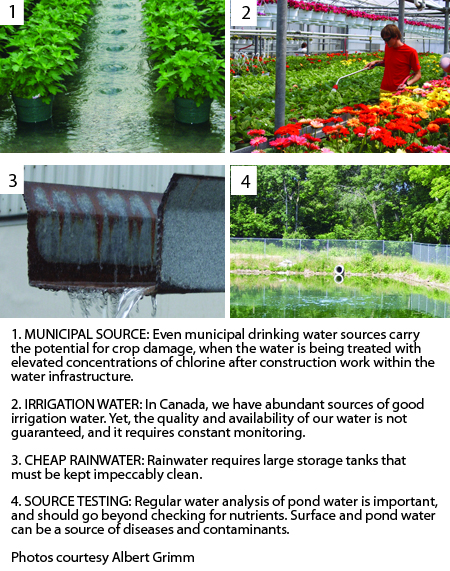

Water and irrigation

Irrigation water quality challenges

January 18, 2008 By Albert Grimm

Growers depend on high quality water, and certain contaminants can create enormous crop problems. Constant

monitoring is essential.

Don’t roll your eyes, at least not yet.

Don’t roll your eyes, at least not yet.

I am not going to tell you about regulations intended for the common good. Neither do I intend to lecture you on the impact that we farmers have on our water resources. Believe me, I don’t like bureaucracy any more than you do. I merely want to share some facts about water, which I think are in the interest of every greenhouse grower – or facts of which every greenhouse grower should be aware.

Our industry might have a very good public relations argument, if we would take a slightly different look at water as a resource. Compared to open field farming, greenhouses have the ability to use far less irrigation water to produce the same crop yields. Where the availability of irrigation water is the limiting factor for agriculture, greenhouses allow for more water-efficient production of a variety of produce. Sometimes local governments even subsidize greenhouse development in drought-sensitive regions.

Even the recycling of irrigation water takes on a totally different dimension when a farmer practises recirculation to save on the cost of getting water, instead of merely trying to comply with discharge regulations. In some very arid climates, the cost of irrigation water is beginning to exceed the cost of fuel, and I would speculate that water efficiency is going to be one of the keywords in the future of crop production. I believe that major trends for the future of greenhouse technology are going to be revolving around water conservation technology, especially because this is going to be a very profitable business. I really think that a lot of money can be made if we can produce more while using less of a costly, valuable – and sometimes scarce – resource.

Wells and rivers don’t have to dry up before water shortages can become an issue. Neither is it merely the pressure from urban populations, with ever-increasing demands for drinking water, which narrows the range of sources for available irrigation water. In greenhouse production, we depend on water of very high quality, and certain contaminants can create enormous crop problems, even at very low concentrations. Not all of these contaminants can be removed economically or effectively. At times, water sources have to be abandoned because they do not allow for profitable production anymore. Consequences can be even more severe if water is not recognized as the cause of problems, and the grower loses money year after year.

In 2002, the Québec Ministry of the Environment published the results of a study that found that, particularly during the summer months, the majority of irrigation water samples drawn from various rivers and wells in rural areas were contaminated with low concentrations of up to 20 different agricultural herbicides. On sensitive crops, some of these herbicides can cause damage, reduced yields, or even crop loss even at extremely low concentrations just above the detection threshold (e.g., Atrazine and Picloram on tomatoes). See sidebar story on page 28 for more on herbicidal damage.

There are other irrigation water issues that are not as elusive as herbicide traces, but they can be equally difficult to solve in a cost-effective manner. Probably the most common problems stem from generally elevated salt levels, from too much sodium or chloride in the water, and from very hard water. If you are faced with such a water source what can you do?

In Saudi Arabia, some greenhouses draw their irrigation water from the ocean. This is made possible with the help of very large reverse osmosis units that separate the salt from the water. And it is made possible by the fact that Saudi Arabia has more oil than water. Reverse osmosis is rather costly and energy intensive and, here in Canada, it is applied only to generate very clean water for the production of extremely sensitive crops like orchids or bromeliads.

Nano-filters employ technology, somewhat similar to reverse osmosis units, but operate at lower pressure and use less energy. They are most effective at removing hardness-causing ions from the water, and less effective at reducing chlorides and sodium. These systems will also remove most herbicide traces and pathogens.

You can consider the installation of large cisterns that collect rainwater from the greenhouse roof. You can then blend the collected rainwater, (or a portion of nano-filtered water) back into the source water, in order to dilute the salts until the water is suitable for irrigation.

Recycling of irrigation water is another option that allows you to reduce the amount of primary irrigation water that you have to draw from your source. It is much easier to remove organic contaminants and/or nutrients from runoff water than to remove herbicide traces or to reduce the salinity or alkalinity of primary irrigation water sources. Recycling of irrigation water is by no means limited to pouring concrete floors, building flood benches, or installing irrigation troughs. As long as you collect at least a portion of the water that drains from your crops, you can treat that water and feed it back into your irrigation system.

Lastly, you can use precision irrigation methods, to reduce the total quantity of irrigation water needed.

Proper water management and production methods that work with minimal drainage can allow you to drastically reduce the amount of water and fertilizer that you apply. If you dose nutrients and water carefully, there is, in principle, no reason why you would have to apply more water to a container-grown greenhouse crop than what evaporates from the container and the plant. Purposeful, regular “leaching” of nutrients is not only without principal benefit, but likely does more harm to the crop than good.

Did you notice that I haven’t touched on filtering and disinfecting water? Particulate matter in the water can plug up your drippers, and it can provide effective food sources for bacteria in water pipes and cisterns. Pathogenic bacteria or fungal spores in the water can wipe out entire crops in a matter of days. In my opinion, however, these are not irrigation water quality issues, but rather a lack of crop maintenance. It should be routine for all greenhouses to install particulate filters and to keep cisterns and pipes free of deposits. It should also be routine to identify all possible sources of pathogens in the water, including those that “breed” the organisms within the installations.

If we have any doubt that our water sources or holding tanks are free of pathogens, we should take steps to properly disinfect them. There are a number of readily available options for treatment, and the cost of losing even part of a crop is almost always more expensive than investing in properly sanitized water.

Albert Grimm is the head grower at Jeffery’s Greenhouses in St. Catharines, Ontario. • abietste@iaw.com

Print this page