I heard once that it takes half a day or longer for some of the largest

ships on our oceans to change course, from the time that the helmsman

turns the rudder until the time that the ship is going into a new

direction.

When at the helm of this ship called IPM, we have to learn to expect the unexpected and roll with the waves

|

|

| MASS TRAPPING Yellow sticky tape is very effective for mass trapping of pest insects. But it can be equally effective at trapping parasitoid wasps. |

|

|

|

| CHEAP BCA Not all biological control agents cost money. But some need getting used to … |

|

|

|

| UNDER CONTROL It is easy to see that this aphid population is controlled by parasitoid wasps, … |

|

|

|

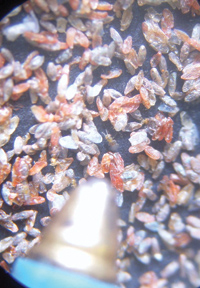

| SMALL, BUT MIGHTY … but can you spot the tiny Trichogramma wasp in this photo? The size of some BCAs makes it difficult to directly observe their effects. |

I heard once that it takes half a day or longer for some of the largest ships on our oceans to change course, from the time that the helmsman turns the rudder until the time that the ship is going into a new direction. Whether these ships reach their destination depends on the experience of the captain, and on his ability to anticipate the reactions of the boat.

Operating a greenhouse feels very much like that. If we make changes to climate or fertilizer schedules, it can take weeks before the plants respond. It is the experience of the grower that determines if plants reach their target.

IT’S LIKE STEERING A SUPER TANKER GOING FULL SPEED IN DENSE FOG

In staying with the same analogy, biological control can feel like steering a super tanker that is going full speed in dense fog, with a radar screen that only works for five minutes a day, while navigating with maps that are full of blank spots. We generally cannot see where we are going, while things are happening way too fast, and we have barely adequate information about the subject. Only if we are very diligent (or very lucky) can we notice unforeseen obstacles, before we crash into them.

Why is that? Traditional pest control, particularly with pesticides, is all about identifying a (single) pest, and finding something that kills this (individual) pest. If other insects (such as other pests) are killed at the same time, that is generally a bonus, but rarely a worry.

CHALLENGES OF LONG-TERM MONOCULTURES OF UNIFORMLY STAGED PLANTS

This unambiguous approach may even work with biological control agents for specific pests under simplified conditions such as long-term monocultures of uniformly staged plants. But it does not work in ornamental greenhouses, where we typically grow a multitude of short-lived crops with multiple stages present simultaneously, and where crops are controlled through constant – sometimes dramatic – changes to physical parameters such as temperature, photoperiod and humidity.

Once we enter into the realm that lies beyond pure chemical pest control, we are dealing not merely with pest-pesticide relationships, but with complex systems and interactions between pests, predators, crops and the environment. If we interfere with any parameter in this system (such as by adding pesticides), we create changes that ripple through the system, and the effects may not only be undesirable, but they are often impossible to predict. To make things worse, when IPM systems crash, we usually cannot even determine with any degree of accuracy what factor was primarily responsible. That is the flipside of the word integrated in IPM.

Beyond pesticides, however, we still need an arsenal of effective emergency breaks to rescue our IPM programs from crashing altogether when stuff goes wrong. Practically all of these emergency tools have negative effects on one or the other biocontrol agent in the system. The trick is to balance the risks and to use the available tools in a manner that allows us to regain our course without wrecking the entire system.

UNDERSTANDING THE PARAMETERS OF MODERN PEST CONTROL

It is not only the effects of synthetic insecticides or other chemicals that we have to consider in a functioning IPM system, but a very wide variety of factors, some of which may not be instantly obvious. Here are some examples of parameters that we have to watch in our new age of pest control:

Yellow sticky traps – Mass trapping with yellow sticky tapes or with numerous large cards is a very effective way to reduce winged pests, particularly western flower thrip. Mass trapping works well as long as we use predatory mites and other non-flying biocontrol agents as the basis of our IPM program. But once we introduce parasitic wasps, predatory midges or predatory beetles, we may catch a proportionally much larger number of beneficials than pest insects on the traps. (Note: small yellow or blue cards for monitoring pest populations are safe for use in almost every application, because they catch no more than a negligible number from any population of beneficial insects.)

Photoperiod – Many of our commercial biological agents are sensitive to short daylengths and do not work well during winter, because they stop to feed and/or to reproduce. In many cases, the response to shorter days is aggravated by cool temperatures.

Temperature – Each biocontrol agent has a unique optimum temperature window, where it outperforms its prey and controls existing populations. In ornamental greenhouses, we are dealing with temperature extremes that are often outside the comfort zone of our biocontrols. As it gets colder, several pests begin to develop much faster than their respective predator, and when it gets very hot in summer, many pests survive high temperatures much better than their natural enemies.

MANY SPECIES OF PLANTS EQUIPPED WITH BUILT-IN CHEMICAL, PHYSICAL DEFENCES

New crops – Many species of plants have developed an amazing array of built-in chemical and physical defences that are designed to keep them from getting eaten by pests. A majority of pest insects have developed effective mechanisms that allow them to learn how to ignore these defences very quickly, in order to be able to feed on a multitude of plants, whenever the preferred food source is scarce. Most predators and parasitoids, however, are much more sensitive to hostile plants, because they never had to develop such adaptation mechanisms. Certain ornamental crops are just too toxic or too hairy for successful biocontrol, and bringing these crops into the greenhouse can disrupt pest control systems, which previously were humming along just fine.

|

|

| Aphids on poinsettias … who’d have thunk? (This is a reference to the last paragraph in this feature.)

|

RESISTANCE TO PLANT TOXINS, RESISTANCE TO CHEMICAL CONTROLS

In fact, the same mechanisms that allow pest insects to become resistant to plant toxins are responsible for the ability of pest insects to become resistant to chemical insecticides. Our biocontrol insects are not equipped with the same adaptability, and therefore the insecticides remain toxic for them, while the same chemical may not affect their target pest anymore.

Practically all pest control chemicals have some negative effect on our biological controls, but some of the pesticides can be useful as emergency breaks without destroying the entire IPM system.

As growers, we have to be very well informed about all interactions between pesticides and IPM systems, and we have to make an effort to understand the details, but it becomes possible to use targeted pesticides effectively and with minimal disruption to the system. Which pesticide to use and how much disruption the treatment creates is less dependent on the mere toxicity of the chemical, but more on the exact mechanism by which the pesticide spares the predators.

Following are some examples of such mechanisms.

For synthetic pyrethroids the answer is simple: There are no such mechanisms. Substances like permethrin (Pounce) or deltamethrin (Decis) are deadly to most commonly used biocontrols. In fact, traces of pyrethroid pesticide residues can kill predatory mites and insects even months after the last application. This group of pesticides is of greatest concern when we try to establish biocontrol programs on plants or in facilities that were previously treated with broadspectrum pesticides.

|

|

| The trick with IPM is to keep limited infestations like this outbreak of two-spotted spider mites from crashing the entire control system.

|

Not all broadspectrum insecticides are entirely unsuitable for biocontrol programs. Dichlorvos (DDVP) for example, does kill practically all beneficial mites and insects, but the active chemical evaporates very quickly and completely from the surfaces of treated plants and structures, and ventilation removes the vapours from the greenhouse. The greenhouse can be safe for biological controls within less than three to four days after application. This pesticide can be useful, if we need to “clean up” a very bad pest infestation that is beyond the reach of any biocontrol program. If we apply it correctly, and if we time a massive reintroduction of biological controls as soon as it is safe after the application, we may be able to successfully restart a failed attempt at biocontrol.

Other chemicals, such as pymetrozine (Endeavor), can be used safely with a large number of biocontrol agents, because their mode of action limits the toxic effects to a few genera of insects. Pymetrozine causes aphids and whiteflies to stop feeding. The insects eventually die of starvation. Predators and parasitoids are safe, because they don’t have the same feeding mechanism. Pymetrozine has limitations, though, because it only works on insects with this particular type of mouthpiece, and it is not very effective when temperatures are lower than 22°C.

INTERFERING WITH THE IMMATURE STAGES

Some insecticides interfere with the development of immature stages of the pest. Examples include pyriproxifen (Distance) and tebufenozide (Confirm). Tebufenozide, in simple words, kills the larvae of certain lepidoptera (caterpillars) by causing them to moult and shed their skin prematurely, before the insect was able to make a new functional skin. Tebufenozide is harmless to most beneficial insects, because these “grow up” without this particular moulting process, but it is also harmless to any pest other than susceptible lepidoptera (moths and butterflies).

It would require a very long list to explain all the details that cause a given pesticide to kill certain insects, while sparing others. This article is certainly not the place to do so. It would also be a very complex list, because we do not have any chemical that kills all insects, and I don’t know of any biological control agent that is not affected by at least one of the pesticides in our arsenal.

|

|

| Interactions between biocontrol agents and pesticides. Does this look complicated to you?

|

For the grower to learn how to work with IPM, it is important to learn and understand as much as possible about the mode of action of each chemical that is used, about the peculiarities and tolerance of each biological control agent, and about the interaction between each of the pest control tools that we have available to us.

It is equally important that we do not get sideswiped by assumptions: e.g., glyphosate (Roundup) is not registered for greenhouse use, but still it was rather surprising to learn that this herbicide is not entirely safe on beneficial mites. Just because a chemical is not labelled as an insecticide does not mean that it is safe on biologicals. It makes me wonder how many other “harmless” farm chemicals interfere unexpectedly with our biocontrol programs.

A few years ago I was equally surprised – when I found an infestation of aphids on my poinsettias in the first season – that we did not spray this crop with insecticides. When we are at the helm of this ship called IPM, we have to learn to expect the unexpected and roll with the waves as well as we can. ■

Albert Grimm is the head grower at Jeffery’s Greenhouses in St. Catharines, Ontario.

• abietste@execulink.com

Print this page