News

Gardens and Landscapes Could Change With the Climate, Say Experts

February 28, 2008 By Eric Shackleton

TORONTO (CP) – Huge watermelons, lush rhododendrons, and cottonwood and sycamore trees could become prevalent in the Canadian landscape if the Earth warms up a few more notches, climate change experts suggest.

TORONTO (CP) – Huge watermelons, lush rhododendrons, and cottonwood and sycamore trees could become prevalent in the Canadian landscape if the Earth warms up a few more notches, climate change experts suggest.

TORONTO (CP) – Huge watermelons, lush rhododendrons, and cottonwood and sycamore trees could become prevalent in the Canadian landscape if the Earth warms up a few more notches, climate change experts suggest.

Backyard gardeners might have to replant their terrain with drought resistant vegetables, flowers and shrubs, while fighting off invasive weeds and nasty bugs.

And native tree species such as maples, members of the boreal forest, might be pushed further north by those of the Carolinian forest as they try to stick to their comfort zone.

Worldwide the Earth’s temperature has warmed up by about 0.7 Celsius over the past 100 years.

In some ways, global warming is a good thing, said Jennifer Bennett, author of Dryland Gardening (Firefly).

“There’s a longer frost-free season… you can grow more things like melons and some of the tomatoes people might not have tried before,’’ said Bennett, who lives near Kingston, Ont.

But there is a downside. “People are really going to see… way more pests and way more diseases because our cold winters normally kill them off,’’ said Bennett. There could also be more drought.

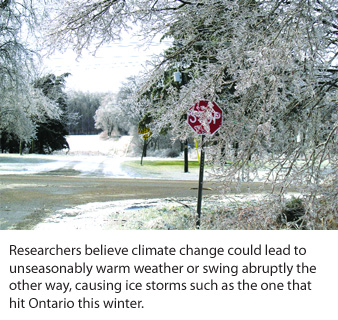

“One of the things that comes with global warming is the extremes,’’ she said. “Sometimes it’s more rain… (or) more drought… more cold.’’

Water shortages are becoming common, said David Hocking, acting executive director of the David Suzuki Foundation, the Vancouver-based environmental group. People might have to get used to brown lawns and put more drought-resistant plants in their gardens to help conserve water, he said.

“When things are hotter, moisture from the soil evaporates faster. You also get more evapotranspiration. The plants are giving off more water and need more water.’’ This leads to a higher strain on the sources of water for communities, whether it’s rivers, lakes or wells, said Hocking. As for pests, milder winters mean many are living longer resulting in massive kills of trees and plants.

In B.C., the mountain pine beetle can now survive in a range where it previously had little chance whatsoever, said Prof. Malcolm Campbell, who teaches cell and systems biology at the University of Toronto.

In the past, “the larvae of the beetle were impeded in thei development by cold winter temperatures,’’ said Campbell, who is involved in a study of how the genetic material of plants responds to fluctuations in temperature and water availability.

“As temperatures have increased the beetle larvae have been able to survive the winters. Therefore there are more of them around to attack the trees the following year,’’ he said.

In general, Campbell said, “trees are going to be subject to a greater level of assault than they’ve ever been before.’’

Trees that are resident in more southern climes might start to grow better in more northern climes. The boreal forest may start to creep north, and conditions will start to be better for the Carolinian forest (characteristic of southwestern Ontario), he said.

Cottonwoods, sycamores and tulip trees might begin to appear more readily in larger swaths of southern Canada as maple trees and pines head further north. This would likely be a slow process.

“We’ve imposed artificial barriers’’ (such as buildings, and highways) “to this happening’’ with any great speed, said Campbell. A contiguous forest would make it much easier for trees’ seed-dispersal agents, such as the wind and squirrels, to do their “planting.’’

Climate change has turned some species, like purple loosestrife brought from Europe by pioneers because it reminded them of home, into invasive weeds.

Purple loosestrife, planted in gardens, didn’t do much because the climate in the early days was not favourable, says horticulturist Daisy Moore, who produces a weekly garden program on radio station 570 in Kitchener, Ontario, and owns a garden design consulting business.

“It didn’t get out of hand for the first 150 years,’’ she said. Then the temperature began to rise and now purple loosestrife is clogging ditches and other wet areas.

There are predictions that if greenhouse gas emissions, such as the production of carbon dioxide by activities like the burning of fossil fuels, continue at the present rate, the Earth’s warming could approach 3 C this century.

Bennett suggests conserving water and planting drought tolerant perennials like asparagus, rhubarb and Jerusalem artichoke.

In early spring, they take advantage of the wet ground before the summer drought arrives, and so don’t need a lot of watering to help produce their fruit, she said. Moore said people should just go on planting root crops like beets, potatoes and carrots.

“Keep in mind though, if it’s a dry summer and you don’t irrigate, the yield will be quite low. But you will still get a harvest.’’ Hocking is rearranging his garden to conserve water, a scarce resource on Bowen Island off the B.C. coast where he lives. A no-watering lawn order is always in effect, he said.

“I’ve got some wet areas in my garden where water naturally moves and I’m moving the plants that get heat stressed and water stressed to those areas. Plants that seem to thrive in drier conditions, I’m moving them to the dry areas.’’ Fraser McClung, a master gardener who has a market garden operation near Port Dover, Ont., on Lake Erie, follows natural methods of controlling pests.

“If you plant a few marigolds in and around the garden,’’ as well as other annuals like nasturtiums, or garlic, or herbs, they will drive off lots of bugs, he said. Aphids and cabbage moths hate nasturtiums. Aphids also can’t stand garlic. The tomato hornworm avoids “big stinky’’ marigolds, as does the white fly.

Master gardener Bill Yeager, who has a Victorian-style garden around his old farmhouse near Simcoe in Norfolk County along Lake Erie, uses peanut shells, bought locally, to mulch his garden.

“You don’t need many of them, just a crust of half an inch to an inch,’’ he said. “They instantly form a protective layer that stops the weeds and keeps the soil moist.’’

Print this page