Features

Biocontrols

Inputs

Biocontrol for broad mites

September 1, 2010 By Rose Buitenhuis 1 Les Shipp 2 and Cynthia Scott-Dupree 3

Broad mites, or Polyphagotarsonemus latus, can be a serious pest of

greenhouse peppers and a wide range of greenhouse ornamental plants

including: gerbera, African violet, cyclamen, begonias, impatiens,

verbena and gloxinia.

Broad mites, or Polyphagotarsonemus latus, can be a serious pest of greenhouse peppers and a wide range of greenhouse ornamental plants including: gerbera, African violet, cyclamen, begonias, impatiens, verbena and gloxinia. Even a few broad mites can cause economic damage to a crop.

|

|

| Leaf damage includes bronzing (Figure 1a). PHOTOS COURTESY DR. ROSE BUITENHUIS Advertisement

|

However, this mite is often hard to detect because of its microscopic size. They are only found when numbers are high and damage is visible.

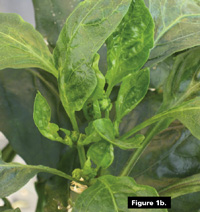

They feed on the underside of young foliage and on developing floral structures (i.e., flower buds), retarding growth and preventing flowers from fully developing. Leaf damage includes bronzing (Figure 1a)and distorted, downward curling of leaves resulting from a phytotoxin secreted by feeding mites. In peppers, young damaged leaves in the growing point curl up on the edge (Figure 1b). Severely infested plants become stunted and may eventually die. Broad mites can be dispersed within a greenhouse by attaching themselves to whiteflies, greenhouse workers or equipment, or by movement of infested plant material into and throughout the greenhouse.

Currently, there are few miticides registered or biological control agents identified for control of this mite pest in Canada. Previous studies in Florida and Israel have demonstrated that predatory mites, such as Neoseiulus californicus and N. cucumeris, can provide biological control of broad mites on pepper crops. However, none of the predatory mites mentioned above are commonly used in Ontario to control broad mites.

SWIRSKII QUICKLY BECOMING PREDATORY MITE OF CHOICE

■ When we started this study, there was anecdotal evidence that the most recently identified predatory mite, Amblyseius swirskii, could provide control of broad mites. Amblyseius swirskii is quickly becoming the predatory mite of choice in many situations because it has a multiple host range that includes thrips and whiteflies, and under certain circumstances it is claimed to perform better than N. cucumeris.

|

|

| In peppers, young damaged leaves in the growing point curl up on the edge (Figure 1b). PHOTOS COURTESY DR. ROSE BUITENHUIS |

Therefore, we decided to determine the potential of A. swirskii as a predator of broad mites in the lab by measuring its consumption and oviposition rate on a diet of broad mites. We also carried out greenhouse trials in two different greenhouse crops, sweet pepper and begonia, to compare the efficacy of A. swirskii with N. cucumeris for broad mite control.

In the lab trials, female A. swirskii were starved for 24 hours and placed on leaf disks with different densities of broad mites. After 24 hours, the number of broad mite corpses was recorded. The maximum consumption rate of A. swirskii was 18 broad mites per day.

A study by another group of researchers found an even higher consumption rate of 30 broad mites per day, which may be a result of slightly different experimental methods.

OVIPOSITION TRIALS POSITIVE FOR SWIRSKII

The results of the oviposition trials showed that A. swirskii can reproduce when fed exclusively on broad mites. The females laid on average 1.2 eggs per day. When A. swirskii feed on other prey such as thrips or on pollen, they produce slightly more eggs, which means that broad mites might not be their optimal prey, but are still a good enough food source for their survival and persistence.

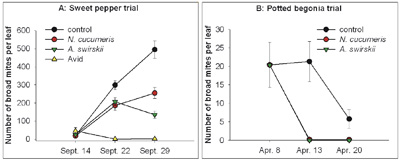

The greenhouse trial on sweet pepper compared the efficacy of A. swirskii for broad mite control to three other treatments:

- Another commonly used predatory mite – N. cucumeris.

- An Avid® (Syngenta Crop Protection, Inc.) foliar spray.

- A non-treated control (Figure 2a).

|

|

| Figure 2 a) and b). Effect of predatory mite applications on broad mite populations in a) sweet pepper and b) begonia greenhouse trials. Release rates of predatory mites: pepper – 60 predators/plant on Sept. 15, 100 predators/plant on Sept. 23; begonia – 25 predators/plant on April 9 and 14. |

Results showed that a single application of Avid immediately suppressed the broad mite population to close to zero and residual effectiveness was evident for three weeks. A. swirskii was more efficient than N. cucumeris in controlling broad mites, however suppression of broad mite populations did not occur until two weeks after the first predatory mite release.

GREENHOUSE TRIALS SHOWED BOTH MITES WERE EFFECTIVE

■ In the greenhouse trial on begonias, A. swirskii was compared to N. cucumeris and a non-treated control (Figure 2b). Both predatory mites were equally effective at controlling broad mite infestations to almost zero within one week of release. After two weeks, no broad mite eggs, immatures or adults were found in the A. swirskii and N. cucumeris treatments. Two weeks after the first release, the predatory mites even spread to the control plots and started suppressing the broad mites there too. The predatory mites were reproducing on the plants as eggs were observed in many samples.

At the end of the trial, control plants showed significantly more damage than plants in the predatory mite treatments. However, while pest suppression of broad mites was very rapid, there was still some damage of the treated plants.

A preventive control program against broad mites is advisable to minimize crop damage, especially because broad mites are difficult to detect in a crop and are often only noticed when damage appears, at which point populations can be very high and spread out through the crop.

An IPM program for broad mites in vegetable and ornamental greenhouse crops (e.g., sweet peppers, impatiens and begonias), emphasizing biological control with the predatory mites A. swirskii or N. cucumeris appears to have substantial potential based on the results of our studies. ■

Acknowledgments: Many thanks to Angela Gradish and Yun Zhang for technical support. This project was funded in part through contributions from the Province of Ontario under the Ontario Research and Development (ORD) program in partnership with Flowers Canada (Ontario). The Agricultural Adaptation Council administers the ORD program on behalf of the province.

1 Vineland Research and Innovation Centre, Vineland Station, Ont.;rose.buitenhuis@vinelandresearch.com

2 AAFC – Greenhouse and Processing Crops Research Centre, Harrow, Ont.; shippl@agr.gc.ca

3 School of Environmental Sciences, University of Guelph, Guelph, Ont.; cscottdu@uoguelph.ca

Print this page