Features

Crop Protection

Inputs

Ultra-sensitive pest monitoring

January 30, 2008 By Lorraine Chan with files from Jennifer Honeybourn

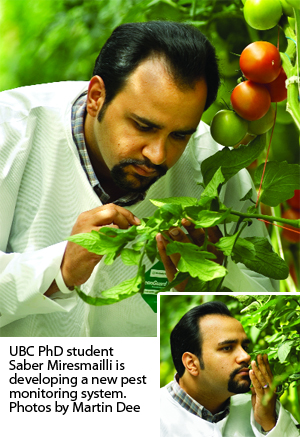

University of British Columbia (UBC) graduate student Saber Miresmailli is devising a monitoring device and sensory system that can head pests off at the pass.

Aphids, spider mites and whiteflies, beware. Your days of pillaging may be over.

Aphids, spider mites and whiteflies, beware. Your days of pillaging may be over.

University of British Columbia (UBC) graduate student Saber Miresmailli is devising a monitoring device and sensory system that can head pests off at the pass. He envisions a sophisticated system that would allow growers to intercept warning signs from plants that forecast problems to prevent outbreaks.

“Some plants emit a kind of SOS chemical signal when they are in distress,” says Miresmailli, a Land and Food Systems PhD student working with Dean Murray Isman. Scientists have shown these signals are produced and emitted in response to herbivores. “We can use these signals to monitor their state of health.”

Agricultural crops, especially greenhouse vegetables, are highly susceptible to pests and diseases. The same conditions that make it worthwhile to grow crops in a greenhouse – heat, moisture and monoculture – are also a boon to herbivore insects. In B.C., the greenhouse vegetable industry generates more than $2 billion annually, but 10 to 20 per cent of those earnings can be swallowed up by pest prevention and crop loss.

While traditional methods of pest monitoring have focused specifically on bugs, Miresmailli’s project shifts attention to the plant itself. At present, pest management programs in greenhouses consist of sticky traps and random spot checks.

“With some greenhouses encompassing more than eight acres, this can be a challenge.”

Zipping around on golf cart-like vehicles, scouts patrol miles of aisles inspecting plants for signs of infestation or disease.

A common foe of tomato plants is the half-millimetre spider mite, which is smaller than a flea, and whose 0.05 mm eggs can only be seen with a microscope.

“By the time these mites are visible to the naked eye, it’s already too late,” says Miresmailli.

Worse yet, he says, these scouts sometimes aid and abet the very bugs they’re hunting. “Workers can inadvertently spread the pests as they move from one plant to another since they pick up the eggs on their tools or clothing.”

When confronted with a pest problem, growers can fight back by releasing predators that eat the pests, or if the infestation becomes too dense, by applying pesticide sprays.

“That’s why I want to invent an alternative,” says Miresmailli. “If we can catch pests before their populations grow exponentially, biological controls such as predatory insects or mites can be more effective.”

Over the next year, Miresmailli will be compiling a database of plant’s chemical compounds, known as volatiles, from both healthy and distressed plants. He has established research agreements with nine commercial greenhouses in Langley, Delta and Abbotsford through the BC Greenhouse Growers’ Association. Miresmailli will collect the volatile samples of three major crops – tomatoes, cucumbers and bell peppers – from the day they’re planted to when they’re discarded.

After analyzing these compounds, he will then isolate the chemical signals that will help the sensory system detect variations and report changes.

Miresmailli will use existing chemo-sensor technology, which has been developed by the military to detect explosives. “They can scan for chemicals in concentrations as low as parts per trillion.”

He aims to couple this sensitivity with a cognitive software program that can analyze environmental factors such as air flow, light, temperature, humidity, time of year and exact geographic location.

“I want to design a holistic system that’s intelligent and intuitive,” says Miresmailli, “one that can read the plant within its environment and indicate when it’s vulnerable long before it’s in actual trouble.”

He says the end result of his research could be a portable, hand-held monitoring device or perhaps a wagon-mounted system that slides back and forth on rails between the long stretches of greenhouse plants. n

Lorraine Chan and Jennifer Honeybourn are communications co-ordinators with UBC public affairs.

This UBC Reports feature (Vol. 53, No. 9) was originally posted Sept. 6, 2007. It is published here with permission.

RESEARCHING WHY SOME BUGS CAN’T GET A GRIP

By Han Nah Kim

Have you ever asked yourself how a plant defends itself from environmental threats, without the ability to run away?

An interdisciplinary group of UBC researchers is studying plant self-defence mechanisms, with a particular focus on plant surface coating.

Led by Reinhard Jetter, an associate professor in botany and chemistry, they are exploring the possibility of replicating protective functions from one plant to another. If they discover what causes the surface of some plants to be slippery for walking insects, says Jetter, researchers might genetically manipulate a crop species to give it a surface that is resistant to insect herbivores.

“The process of reproduction could further be used in materials production,” says Jetter, “perhaps to even discover in the long run a substitute for plastic coatings.”

Jetter and his team, which includes biology and chemistry graduate students, are examining not only the chemical make-up of plant surfaces, but also the genes and enzymes responsible for it.

This UBC Reports feature (Vol. 53, No. 9) was originally posted Sept. 6, 2007. It is published here with permission.

Print this page