Features

Flowers

Research

Retail

Trends

Selling plants with a purpose: Greenhouse ornamentals for pollinator gardens

In the world of pollinator gardens, is there a place for greenhouse ornamentals?

August 17, 2021 By Dr. Sarah Jandricic, Famke Alberts, Rodger Tschanz and Dr. Al Sullivan

Non-native plants can be very attractive to local pollinators. The Cosmos pictured here is a great example of a non-native plant species which attracts native bees in Ontario. Photo credit: M. Boucher, OMAFRA

Non-native plants can be very attractive to local pollinators. The Cosmos pictured here is a great example of a non-native plant species which attracts native bees in Ontario. Photo credit: M. Boucher, OMAFRA For many, a home garden is a place of comfort and beauty. But for the past several years there’s been rising demand for gardens that serve a purpose. A great example of this is the COVID-spurred resurgence of Victory Gardens, which not only produce vegetables and herbs, but also boost morale.

Gardening with purpose can also mean contributing to the world around us. Planting ornamentals that provide nectar or pollen to pollinators in urban environments is a popular way to support the local ecosystem. Unfortunately, attempting to find the “right” or “best” plants to support pollinators can lead growers (and homeowners) down an internet rabbit hole. Many websites try to simplify things by promoting the exclusive use of local native plants – but does that mean Ontario growers have to switch up what they grow to capitalize on this trend?

With the help of researchers at the University of Guelph, summer students at the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA) have spent several years trying to answer this question: “In the world of pollinator gardens, is there a place for ornamentals commonly grown by Ontario’s greenhouses?” After three years of watching insects fly by, we think we have a definitive answer!

Counting six-legged visitors

Each year, we selected 10 “exotic” plant species, meaning they originated outside of Canada and the continental U.S. We directly compared these to 10 species of native plants. Specifically, we used “nativars” – cultivars of native plants that have been somewhat altered by the ornamental industry for aesthetics – to provide a more apples-to-apples comparison. Although we attempted to choose the same plant species each year, availability from suppliers donating to the trial differed somewhat year-to-year. But all species chosen – whether exotic or native – can typically be found in local greenhouses or nurseries in Ontario.

Trials were run at the University of Guelph, as part of the university’s bedding plant trials in 2016 and 2018, and at the Landscape Ontario office in Milton, Ont. in 2020. Students watched small plots of individual plant species for specific time intervals, and recorded the number and type of pollinators they saw.

The view from above showing a plot of exotic plants tested.

Standout exotics and nativars

So, after three years, what did we find?

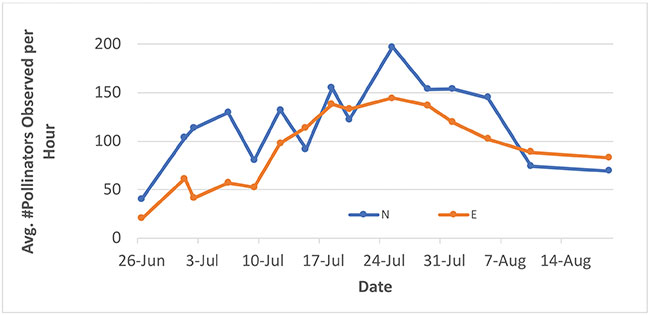

If we look at the average number of pollinators observed on similar observation dates over three years at both trial locations (Guelph and Milton), we see a trend towards native plants being more attractive to pollinators (Figure 1). This is especially apparent early in the season around late June to early July, and again in late July.

Figure 1. Average pollinator visits per hour per square metre of native (N) or exotic (E) plant species, taken on similar observation dates over a three-year trial.

Overall, we observed an average of 117 pollinator visits per hour per m2 in plots filled with native plants. This average was lower at 96 pollinator visits per hour in plots of exotic plant species.

Despite this trend, however, the difference between the two plant categories wasn’t statistically meaningful – mostly because we saw a lot of variation in attractiveness depending on the actual plant species involved.

If you remember the last time we reported on this research (see “Annuals and Perennials That Cause a Buzz” in the November 2018 issue of Greenhouse Canada Magazine), you’ll recall that in both the native and exotic plots, there were species that performed well and those that performed poorly – despite careful selection of plants that we thought would be successful.

In an example from our 2020 data, native plants like Helianthus and Coreopsis attracted some of the highest total numbers of pollinators of all the plants tested, with more than 650 pollinator visits each over the summer. But, other native plant species like Monarda and Gaura (with the common names Bee Balm and Bee Blossom, respectively) attracted very few pollinators comparatively, at fewer than 90 total pollinator visits each. What this ultimately means is that, when it comes to pollinators, generalizations about plants (“native plants good, exotics bad”) is a trend that needs to go the way of the dinosaur.

Instead, our research has shown us that there are both good and bad selections of exotic species for growers who are interested in producing and promoting more pollinator-friendly plants as part of their spring-crop selection. Based on our three years of data, we’ve compiled a list of the top eight exotic plant species (four annuals and four perennials) and top eight nativar plants (all perennials) in terms of pollinator attraction, when tested in suburban areas of Ontario.

TABLE 1. These exotic and nativar species attracted the most pollinators during three year trials in Southern Ontario. Plants that attracted high numbers of native bees are indicated in bold, as they are often of most interest to consumers.

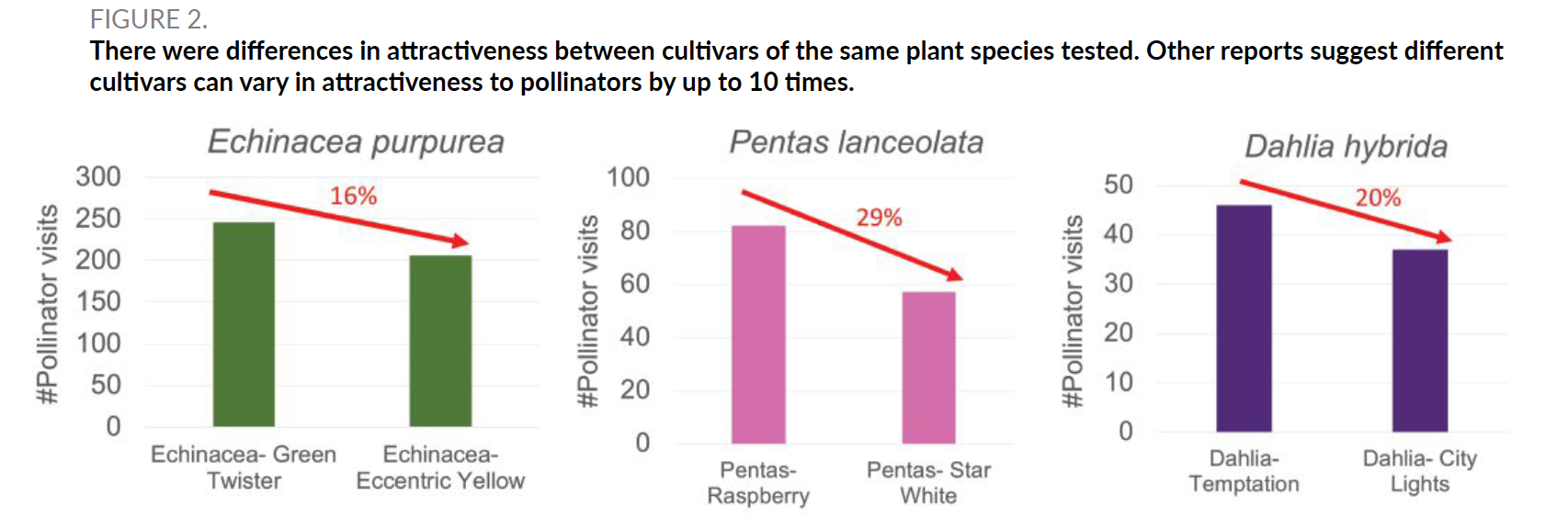

As both abundance (total number of pollinator visits) and diversity (kinds of pollinators) are important from a pollinator garden perspective, we kept this in mind while making this list. Exotic plants that attracted a moderate number of total pollinator visits were still included if they attracted more “rare” pollinators such as bee flies, hawk moths, and pollinating beetles. We also made sure to include cultivar information, as our data and other research demonstrate that variety can also play a significant role in pollinator attraction (see Figure 2). This could be due to changes in volatiles, amount of pollen or nectar, or the colour perceived by the insect. Extensive testing is being done by Michigan State and other U.S. institutions on this front. They suggest watching for specific cultivar recommendations from breeders or extension publications to get the best bee- or butterfly-friendly variety.

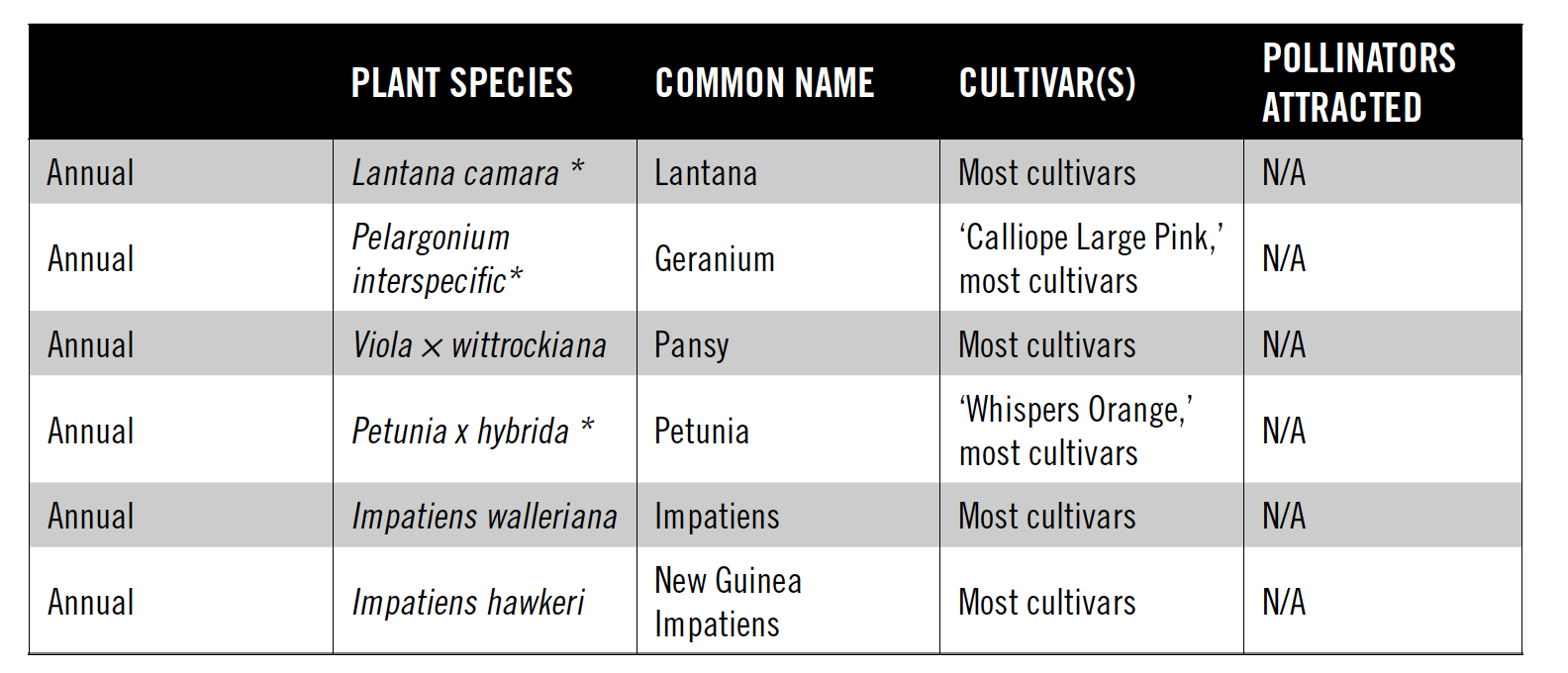

Although our list is not exhaustive, it does provide a starting guide to what growers can confidently promote as pollinator-friendly spring crops. It could also serve as a guide to customize higher-value mixed containers for garden centres. To help avoid missteps, we’ve also compiled a “No-fly” list of exotic plants that do not attract any kind of pollinator. This is based on our research, and is backed up by similar research done by Michigan State University.

TABLE 2. Exotic plant species that consistently do not attract a high number of pollinators, in terms of abundance or diversity. These plants should be avoided in sales of mixed containers or flats promoted as “pollinator-friendly.” (*tested in Ontario)

The bottom line of our study is, if we want to capitalize on pollinator gardens as a trend, flower growers don’t need to grow more native plants to satisfy customers. Instead, they need to expand their definition of “pollinator-friendly” plants to include exotic ornamentals and help educate the buyer. Ultimately, using mixes of plants – native and exotic, annual and perennial, tall and short, early and late flowering – creates the kind of pollinator garden that supports many and different types of pollinators throughout the gardening season. And looks good while doing it.

Sarah Jandricic, PhD, is the greenhouse floriculture IPM specialist for OMAFRA. Famke Alberts is a fourth-year student at McMaster University and was part of the Summer Employment Opportunity program at OMAFRA in 2020. Rodger Tschanz is the trial garden manager at the University of Guelph (UofG), and Al Sullivan, PhD, is Professor Emeritus at UofG. Land was provided by The University of Guelph in 2016 & 2018, and by Landscape Ontario in 2020. Special thanks to the plant breeders who donated plant material for these trials.

Print this page