Features

Biocontrols

Inputs

IPM: Prevention And Early Intervention

This starts with awareness of ‘potential’ threats, using your experience to be on the lookout for incoming pests, and putting processes in place to facilitate early detection and/or early action to mitigate them.

May 25, 2017 By Drs. Michael Brownbridge and Rose Buitenhuis

June 2017, Vineland, Ont. – This is Part 2 in a six-part series of articles on thrips (and other pests) integrated pest management, where we will provide practical application tips and tricks, information on new technologies and how it all fits within an overall IPM program.

Each article will be accompanied by a short video demonstrating a technique or principle. The content of this series is based on research performed at Vineland Research and Innovation Centre and is supplemented with ‘information from the field,’ contributed by colleagues using biocontrol strategies in greenhouse production. For more information on specific biocontrol agents or IPM in general, see www.greenhouseIPM.org.

The mantra of IPM is “start clean, and stay clean.” To be successful in biocontrol, actions need to be taken early and often before pests are readily detected in a crop. Biocontrol agents function most efficiently when pest numbers are low; they prevent damaging populations from developing. Furthermore, biocontrol agents will work best when deployed within a system that supports their success (Fig 1).

Consider the system: By definition, the systems approach is a pest management strategy where the influence of all factors affecting pest abundance is considered, with the goal of creating a system that is fundamentally more robust. In an ideal system, pests rarely reach damaging levels, plants are better able to tolerate feeding injury and conventional pesticides are rarely required.

However, if we do not understand the reason why there are pest outbreaks, we will always face a recurrent pest problem. Fixing a situation that is innately flawed takes a lot of effort (and money). It is a little like a jigsaw puzzle – there are many different pieces and understanding how each of these relate to and influence each other is critical to successful crop production and use of biocontrol strategies within that production system.

Pest-free environment: It is important to take preventive steps from the very beginning of a crop production cycle, ensuring that the growing environment that young plants are brought into is clean and free from pests and diseases. Implementation of good sanitation practices after a crop cycle and prior to installation of new plants is just good working practice. No residues should remain from previous crops, benches and floors should be disinfected, weeds under benches removed and algae cleaned from the floor. All can serve as sources of infection or infestation; making sure that the greenhouse is clean from the get-go helps on many levels.

Use of screens over vents and fan intakes is probably the single most effective way to prevent the entry of many pests into the greenhouse. Mesh size is important, and use of screens will affect airflow (and cooling) through these vents or intakes. However, there are many useful resources (online and other) available to help calculate the type of screen needed, and how to install to prevent any impediment of air movement.

Healthy and resistant plants: It is also extremely beneficial to understand the relative susceptibility of different plant species and varieties to pests and diseases before they are grown. Knowing what to expect allows you to pre-plan a pest management program. Experience from previous years can help inform the plan, and can play an important role in the selection of certain cultivars for production. While the decision to grow some cultivars over others is primarily dictated by what the market wants, rather than pest management programs, there may be some latitude whereby it would make sense to select resistant or tolerant cultivars over more susceptible ones. If some cultivars are known to be susceptible, that knowledge can be used to guide scouting and management interventions. Work by Dr. Sarah Jandricic (OMAFRA) showed that some ornamentals could harbour high thrips infestations without showing a lot of damage. It is important to identify and control these hidden hot spots before the thrips move on to more susceptible plants.

Equally important is the use of production practices that optimize nutrient and water inputs to grow healthy plants. For some plants, use of high fertilizer rates, or application of high-N fertilizers should be avoided. There is a known link between fertilizer rate and population growth of pests like thrips and aphids. Although most greenhouse crops are on high-fertilizer regimes, not all plant species need these high rates. Research suggests that in some crops fertilizer can be reduced by 33 to 75 per cent without affecting quality, but this can have a dramatic effect on susceptibility to pests and diseases. Similarly, plants that are over-watered or water-stressed are more vulnerable to pests. Use of best practices will help create a more resilient crop that is more productive and inherently less prone to pests and diseases, and biocontrol then becomes a component that functions much more efficiently within that system.

Early start of biocontrol: Pests are excellent hitchhikers and travel around the world anywhere plant material is shipped. Despite the best efforts by propagators to deliver clean material, pests may be coming in on propagative plant material like cuttings, plugs or seedlings. We know that cuttings frequently carry low numbers of pests such as thrips or whitefly.

In 2009, Wendy Romero at the University of Guelph sampled cuttings of six chrysanthemum cultivars over a seven-month period. She found an average of eight to 28 thrips per 100 cuttings.

More recently (summer 2016), we counted pests on a few batches of chrysanthemum cuttings. Out of 13 batches of mum cuttings tested, 12 of these (i.e. 92 per cent!!!) were infested with either spider mites, thrips or both. We detected as many as 76 thrips per 100 cuttings. Although these numbers are alarming, detection of these insects in what may be thousands of cuttings or seedlings is like looking for the proverbial needle in the haystack and with cryptic pests like thrips, the problem is made worse by the fact that they lay their eggs in plant tissue.

Given that most propagation facilities for ornamentals continue to rely heavily on pesticides, any pests that arrive on cuttings are likely to have been exposed to a range of different chemistries so the efficacy of many registered products in Canada may be compromised. In these crops, growers should assume that incoming cuttings will carry some pests. The decision, then, is to act immediately; no waiting for sticky card catches to reach a certain threshold.

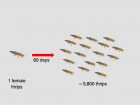

For pests like thrips and whiteflies, by the time you see them in the crop (or on sticky cards for that matter) it is probably too late to achieve success with biologicals. Most of the highly successful pests (thrips, whiteflies, spider mites, aphids) have extremely rapid life cycles and high reproductive potential. Populations can go from a few to a lot very quickly (Fig 2). Clearly, the earlier we can intervene, the more likely a bio-based IPM program is to be successful.

A strategy often used in the early stages of crop production is to ‘front load’ a biocontrol program. The goal is to mitigate problems early by overwhelming pests with an army of biologicals. In vegetable production, seedlings are often treated with biocontrol agents at the propagator. Good examples are the use of biopesticide drenches like Rootshield®, which is applied early to prevent root diseases on developing roots, and the use of predatory mite sachets on a stick that is placed directly in the rockwool blocks.

During early growing stages of both vegetables and especially ornamentals, plants are small and generally grown close together. As a result, good crop coverage, e.g. with predatory mites like Neoseiulus cucumeris, can be achieved relatively easily and a comparatively small amount of product is needed to cover all the plants. Some biocontrol agents, like Dalotia (=Atheta), N. californicus and soil predatory mites, will establish without the need for further introductions, others will have to be released on a regular basis throughout the production cycle.

Another way to control pests early is through the use of cutting dips. This approach has potential for many ornamental crops that are started from cuttings. Cuttings are immersed in low-risk (bio)pesticides such as insecticidal soap, horticultural oil or BotaniGard (Fig 3). Immersion of batches of cuttings provides thorough coverage, is quick and effective, uses relatively little product, and is readily integrated into the work flow. In a case study using poinsettia cuttings carrying Bemisia whiteflies, dipping in a mixture of BotaniGard and Kopa insecticidal soap eliminated around 70 per cent of a starting population and reduced it to levels that were suppressed thereafter with other biocontrol agents. Results from these trials are being used to get this method of application on to the label of these materials. We are also expanding the work to validate this method for other hitchhiking pests such as thrips and spider mites and other propagative crops such as chrysanthemums, mini roses, ivy, bedding plants, etc.

Click here for a video presentation on the correct application of cutting dips.

The most frequent questions asked about this approach are related to potential risks of phytotoxicity and disease transfer among cuttings that are immersed in a ‘communal bath.’ Immersion of poinsettia cuttings in oils and soaps prepared at the recommended spray rates (one to two per cent) caused damage to the leaves; the severity of damage was correlated to the concentration used and there were also differences in cultivar sensitivity. We also considered risks of disease transfer, specifically Pectobacterium (Erwinia) carotovora. Based on results from our trials, the level of risk appeared to be very low, but it is good practice to change the dip suspension periodically to prevent the potential buildup of inoculum to infectious levels, and to thoroughly clean and sanitize the dip bath after use.

THE LAST WORD

Prevention and early intervention strategies are key components in IPM, and are especially important when biological control forms the basis of a pest management program. This starts with awareness of ‘potential’ threats, using your experience to be on the lookout for incoming pests, and putting processes in place to facilitate early detection and/or early action to mitigate them. Use of cultural practices that minimize pest buildup wherever possible will support the successful implementation of a biocontrol strategy. Pest outbreaks may still occur, but if you start out right and build resilience into the production system, pest pressures will be reduced and you will set yourself up for success.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Researchers and technical staff who participated in the research: Dr. Sarah Jandricic, Graeme Murphy, Taro Saito, Mark Jandricic, Ashley Summerfield,

Angela Brommit, Paul Côté, Dr. Michelangelo LaSpina, Anna Krzywdzinski, Rebecca Eerkes and Erfan Vafaie.

This project was funded in part through Growing Forward 2 (GF2), a federal-provincial-territorial initiative. The Agricultural Adaptation Council assists in the delivery of GF2 in Ontario. Dümmen, BioWorks, Koppert Canada, Flowers Canada (Ontario) Inc. (Guelph, ON, Canada), provided additional support.

We hope you are looking forward to the next articles in this series. We appreciate feedback, so if you have any suggestions for topics, or comments, please let us know (Rose.Buitenhuis@vinelandresearch.com; Michael.Brownbridge@vinelandresearch.com).

Print this page