The winter harvest, as we practice it at Four Season Farm, has three

components: cold-hardy vegetables, succession planting, and protected

cultivation.

The following is an excerpt from, The Winter Harvest Handbook: Year-Round Vegetable Production Using Deep Organic Techniques and Unheated Greenhouses. It is written by Eliot Coleman, a grower with considerable expertise in low-technology greenhouse production. The book provides a practical model for supplying fresh, locally grown produce during the winter season, even in climates where conventional wisdom says it “just can’t be done.”

Choosing locally grown organic food is a sustainable living trend that’s taken hold throughout North America. Coleman helped start this movement with The New Organic Grower published 20 years ago.

The winter harvest, as we practice it at Four Season Farm, has three components: cold-hardy vegetables, succession planting, and protected cultivation.

|

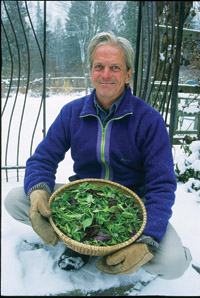

| Typical midwinter scene on a four-season farm.

|

Cold-hardy vegetables are those that tolerate cold temperatures. They are often cultivated out of doors year-round in areas with mild winter climates. The majority of them have far lower light requirements than the warm-season crops.

The list of cold-hardy vegetables includes the familiar – spinach, chard, carrots, scallions – and the novel – mâche, claytonia, minutina and arugula. To date there are some 30 different vegetables – arugula, beet greens, broccoli raab, carrots, chard, chicory, claytonia, collards, dandelion, endive, escarole, garlic greens, kale, kohlrabi, leeks, lettuce, mâche, minutina, mizuna, mustard greens, pak choi, parsley, radicchio, radish, scallions, sorrel, spinach, tatsoi, turnips, watercress – which at one time or another we have grown in our winter-harvest greenhouses. (The most promising vegetables, those with which we have the most experience, are discussed individually in chapter 8.) The eating quality of these cold-hardy vegetables is unrivalled during the cooler temperatures of fall, winter and spring. They reach a higher level of perfection without the heat stress of summer.

|

|

| The author’s farm. Photos by Barbara Damrosch. |

Succession planting means sowing vegetables more than once during a season in order to provide for a continual harvest. The choice of sowing dates, from late summer through late fall, and winter into spring, keeps the cornucopia flowing. In midwinter, the vigorous regrowth on cut-and-come-again crops provides the harvest while late-fall-and-winter-sown crops slowly reach productive size.

We begin planting the winter-harvest crops on Aug. 1, the start of what we call the “second spring.” We continue planting through the fall. The reality of sowing for winter harvest is that the seasons are reversed from the usual spring-planting experience. Daylength is contracting rather than expanding; temperatures are becoming cooler rather than warmer. Success in maintaining a continuity of crops for harvest through the winter is a function of understanding the effect of shorter daylength and cooler temperatures on increasing the time from sowing to harvest. Thus, the choice of precise sowing dates for fall planting is much more crucial than for spring planting. The dates are also very crop specific, and I’ll explain this in more detail in chapter 4.

|

|

| Tomatoes continue growing in the mobile greenhouse while winter crops have just been planted outside. Photos by Barbara Damrosch |

GOAL OF NEVER LEAVING A GREENHOUSE BED UNPLANTED

We aim for a goal of never leaving a greenhouse bed unplanted, and we come pretty close. Within 24 hours after a crop is harvested, we remove the residues, re-prepare the soil, and replant. We keep careful records so as to follow as varied a crop rotation as possible.

Protected cultivation means vegetables under cover. The traditional winter vegetables will often survive outdoors under a blanket of snow. Since gardeners can’t count on snow, the best substitute is shelter of an unheated greenhouse. Many delicious winter vegetables need only that minimal protection.

|

|

| Any type of lightweight floating row cover that allows light, air and moisture to pass through is suitable for the inner layer material in the cold houses. Photos by Barbara Damrosch. |

|

|

|

| A mid-winter salad mix … fresh from the greenhouse. Photos by Barbara Damrosch |

Our winter-harvest cold houses are standard, plastic-covered, gothic-style hoop houses. The largest of our houses are 30 feet wide and 96 feet long. They are aligned on an east-west axis. For the most part, the cold houses need only a single-layer covering of UV-resistant plastic, whereas heated greenhouses benefit from two layers, which are air-inflated to minimize heat loss.

The success of our cold houses seems unlikely in our Zone 5 Maine winters where temperatures can drop to –20°F (–29°C). But our growing system works because we have learned to augment the climate-tempering effect of the cold house itself by adding a second layer of protection. We place floating row-cover material over the crops inside the greenhouse to create a twice-tempered climate. The soil itself thus becomes our heat-storage medium, as it is in the natural world.

INCORPORATING A LIGHTWEIGHT FLOATING ROW COVER

Any type of lightweight floating row cover that allows light, air and moisture to pass through is suitable for the inner layer material in the cold houses. The row cover is supported by flat-topped wire wickets at a height of about 12 inches (30 cm) above the soil. We space the wickets every four feet (120 cm) along the length of 30-inch-wide (75 cm) growing beds. The protected crops still experience temperatures below freezing, but nowhere near as low or as stressful as they would without the inner layer. For example, when the outdoor temperature drops to –15°F (–26°C), the temperature under the inner layer of the cold house drops only to 15°F to 18°F above zero (–10°C to –8°C) on average. The cold-hardy vegetables are far hardier than growers might imagine and, in our experience, many can easily survive temperatures down to 10°F (–12°C) or lower as long as they are not exposed to the additional stresses of outdoor conditions. The double coverage also increases the relative humidity in the protected area, which offers additional protection against freezing damage. The climate modification achieved by combining inner and outer layers in the cold houses is the technical foundation of our low-input winter-harvest concept.

In a world of ever more complicated technologies, the winter harvest is refreshingly uncomplicated because all three of these components are well known to most vegetable growers. What is not well known is the synergy created when they are used in combination, and that is what we continue to explore on a daily basis on our farm. ■

Elliot Coleman and his wife Barbara Damrosch were hosts of The Learning Channel’s popular series, Gardening Naturally. Today, Coleman and Damrosch operate a year-round commercial market and garden and conduct groundbreaking horticultural research projects at Four Season Farm in Harborside, Maine. They have been featured in numerous publications, including Martha Stewart Living, The New York Times, House and Garden, Mother Earth News, The Boston Globe, Organic Gardening, Publisher’s Weekly, and Library Journal, among others.

The Winter Harvest Handbook features 100 full-colour photos and illustrations. For more information on the book, visit www.chelseagreen.com. To order in Canada, the book is $37.50, and can be ordered through a Canadian bookstore or online, or through University of Toronto Press Distribution at 800-565-9523.

Print this page