Features

Biocontrols

Inputs

Greenhouse Grower Notes: Influencing predatory mites

April 4, 2008 By Gillian Ferguson

Study looked at number of eggs laid daily and total number of prey or eggs killed

My last article in this magazine described the categorization of Phytoseiid mites (family to which many commercially available predatory mites belong) into three major lifestyles or categories – Type I, II and III.

To recap, a Type I predator (e.g., Phytoseiulus persimilis) feeds specifically on mites belonging to the genus Tetranychus (e.g., Tetranychus urticae or two-spotted spider mite).

A Type II predator is usually associated with species that produce dense webbing, but they may also feed on other types of mites such as russet and cyclamen mites, and are therefore not as specialized as Type I predators. Type II predators include Galendromus occidentalis, Neoseiulus californicus, and N. fallacis.

A Type III predator is a generalist predator because it feeds on a much broader range of food. Species in this category include Amblyseius andersoni and A. swirskii.

This article will focus on one Type I and two Type II species, i.e., P. persimilis, N. californicus, and G. occidentalis. It summarizes work done by University of California researchers (D.D. Friese and F.E. Gilstrap) in the early 1980s on the influence of prey availability on reproduction and feeding of these predators.

|

| Adult spider mite with recently laid eggs. Photos courtesy Gillian Ferguson, OMAFRA |

|

| Predatory mite, Phytoseiulus persimilis, feeding on spider mite egg. |

GENERAL TRIAL DESCRIPTION

Recently moulted and mated female P. persimilis, N. californicus, and G. occidentalis were individually held in the laboratory at about 26ºC, 50 per cent RH, and with a light period of 14 hours. Each day for the duration of their lives, females were offered five levels of prey, which consisted of 1, 3, 5, 10, or 40 eggs of Tetranychus cinnabarinus, otherwise known as carmine mite. (As an aside, the naming or taxonomy of this mite is uncertain because some scientists consider the carmine mite to be distinct from the two-spotted spider mite [T. urticae], whereas others consider them to be the same species). All females were observed for several factors, including number of eggs laid daily and the total number of prey or eggs killed.

RESULTS OF THE TRIAL

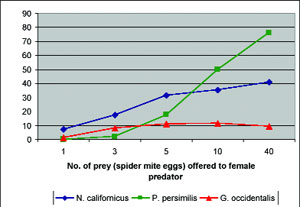

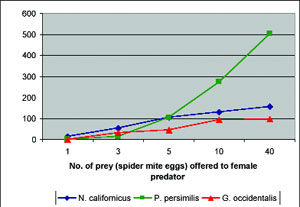

Generally, at the lower levels of available prey, N. californicus laid more eggs than the other two species (Figure 1). When the prey level was 1, N. californicus laid 7.3 eggs, G. occidentalis laid 1 egg, while P. persimilis did not lay any eggs. However, at the level of 10 prey eggs and above, P. persimilis surpassed the others in its egg production. Similarly, when the prey level was 1, P. persimilis did not kill any prey or spider mite eggs, whereas N. californicus and G. occidentalis killed 0.9 and 0.5, respectively (Figure 2). At the level of 10 prey eggs and above, P. persimilis killed many more prey than the other two species. At the highest prey level, G. occidentalis was the lowest performer in both sets of observations. In particular, the increase in the number of prey did not significantly increase its egg-laying capacity relative to the other two predators (Figure 1).

|

| Figure 1. Influence of prey (spider mite eggs) availability on total eggs laid by female predatory mite under standard laboratory conditions |

|

| Figure 2. Influence of prey (spider mite eggs) availability on total prey (spider mite eggs) killed by female predatory mite under standard laboratory conditions. |

These results indicate that when prey levels or spider mite populations are low, it may be more strategic to release N. californicus, and when populations are on the rise, P. persimilis is likely to be the more efficient predator. However, these results were obtained under laboratory conditions, and certainly, other environmental factors can play a role in modifying the responses of the various predators. Some of these factors include effects of higher or lower temperatures, lower RH levels, and surface characteristics of different host plants.

Gillian Ferguson is the greenhouse vegetable IPM specialist with the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs in Harrow. • 519-738-1258, gillian.ferguson @ontario.ca

Print this page