Features

Biocontrols

Inputs

Friendly but deadly: Getting to know your mycoinsecticides

The what, whys and hows of using fungal pathogens against insect pests.

September 18, 2018 By Dr. Daniel Peck

Whitefly pests of greenhouse crops are a susceptible target for mycoinsecticides.

Whitefly pests of greenhouse crops are a susceptible target for mycoinsecticides. Insect pests don’t always die by flipping over with six legs in the air. In nature, the process is sometimes an inescapable decline due to an overwhelming infection, followed by loss of appetite, disinterest in reproduction, lethargy, and then death. Science has learned to isolate, select and mass-produce some of these infectious microbes.

Among them are the entomopathogenic fungi, which are certain uncommon strains of fungi that can operate as insect parasites. These biocontrol organisms are in a class of pest management products called mycoinsecticides. This article will help you to understand them and help you to make the best use of them in your plant-protection toolbox.

What’s a mycoinsecticide?

A mycoinsecticide is a microbial insecticide whose active ingredient is a living fungus that is pathogenic to insects or other arthropod pests. When the spores land on the insect’s cuticle, they receive cues to germinate, then penetrate the host, overwhelm its defences and kill it. Some specific strains also release metabolites while inside the pest that may also injure or kill it. Both are pretty sophisticated, or at least complicated, approaches. As such, the development of resistance to the mycoinsecticidal modes of action are highly unlikely. Rotating or substituting conventional chemical insecticides with mycoinsecticides will therefore delay or prevent the development of insecticide resistance.

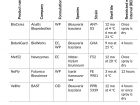

Only specific rare fungal strains have been developed as commercial mycoinsecticides. In general, these strains have been selected from tens to thousands of others for, among other things, their virulence, speed of kill, and ability to be mass produced through large-scale production processes. Five commercial products are currently available for greenhouse use in Canada (see Table, pg.18). These specific commercial strains represent the fungal species Beauveria bassiana, Isaria fumosorosea (formerly Paecilomyces fumosoroseus) and Metarhizium brunneum (formerly M. anisopliae). Beyond species and strain, the end-use products can vary in a range of ways based on their formulations, shelf lives, spectrum of susceptible pest targets, labeled uses and recommended use patterns. Other considerations for choosing from among these products is their compatibility and interactions with other plant protection tools such as beneficial insects and mites (predators and parasitoids) and traditional chemical insecticides or adjuvants. Adequacy of access to technical support from the manufacturer/distributor should also be considered.

Why you might use one

Consider these five reasons for why growers choose to use – and continue to use – mycoinsecticides

- There is increasing market demand by consumers and retailers for inputs that are more biologically-based.

- Mycoinsecticides have far fewer safety concerns for workers, consumers and the environment because of their low toxicity.

- The relatively brief Restricted-Entry Intervals (REI, 4-12-hour) and short Pre-Harvest Intervals (PHI, 0-day) are very favourable for production management.

- Their complex modes of action on target pests will prevent or delay development of resistance to synthetic pesticides.

- Mycoinsecticides are generally more compatible with the use of beneficial insects and mites.

Take time to reflect on which of these features might influence your decision to use mycoinsecticides.

How they work

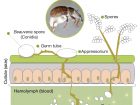

The basic mode of action for most mycoinsecticides consists of six general phases: attachment, germination, penetration, invasion, replication and host death. When the formulated product is diluted and applied following labelled instructions, spores can land on and attach to the target host’s cuticle. Adhesion largely occurs by hydrophobic interactions between the cuticle and the spore. Efficacy depends on the number of spores that end up attached to the host’s body. In response to chemical cues on the cuticle, the spore will germinate and then develop an appressorium, which is the penetration structure. Through a combination of mechanical pressure and degradation from a mixture of enzymes, the fungus penetrates through the layers of the cuticle.

Certain strains of Beauveria have additional modes of action involving the release of one or more metabolites inside the pest. Once in the body cavity these specific strains will release metabolites such as beauvericin, which is a toxin that weakens the insect’s immune system. They can then release oosporein, which is an antibiotic that helps the fungus outcompete the insect’s gut bacteria. At this point the fungus will proliferate within the body cavity in the form of blastospores, which are the kind of spores that are formed in a liquid environment. Under special circumstances, such as higher humidity, there will be a seventh phase that entails outgrowth from the inside to the outside. This external sporulation produces conidia, which are spores formed in and spread through the air.

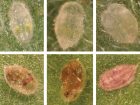

Because the conidia are available to infect another generation of insect hosts, this is how the fungus would complete its life cycle in the natural environment. Our experience with B. bassiana strain GHA, however, is that growers should not use external mycosis as a measure of success. In other words, growth on the outside is not a good measure of insect mortality. In most cases the fungus will not emerge from the body and produce a white cottony mass, yet it has still killed the insect. Sometimes the only sign of death by fungal infection is lack of movement and a discolouration of the body. In soil and foliar applications in the greenhouse, mycoinsecticides will not take off to reproduce and establish on their own. They will not disrupt soil microbial communities, persist in the environment, or lead to any substantial infection from one host to another. Therefore, to keep pest populations suppressed, mycoinsecticides should be reapplied every three to ten days.

Commercial mycoinsecticides vary in their spectrum of activity, meaning the range of target insects that are known to be susceptible to the particular strain. Activity against only a single pest species means that the strain may not be commercially viable given the small potential market. On the other hand, non-target activity against pollinators, predators and parasitoids is highly undesirable. Application practices, such as not spraying when beneficials are present or pollinators are foraging, can reduce those risks. And when you do spray, make sure you follow label guidelines for personal protective equipment (PPE) to keep yourself safe. Although biologically based and low in toxicity, mycoinsecticide applicators are still required to use long-sleeved shirts, long pants, eye goggles, shoes plus socks, waterproof gloves and NIOSH approved respirators/masks, the latter as a precaution against developing a rare sensitivity to the living active ingredient.

Making the most of your application

To get the most out of your mycoinsecticide application, keep in mind the following best-use practices.

Stay aware of the appropriate storage conditions and the shelf life expectations. As these are living organisms, storage conditions may be more particular and shelf life may be shorter.

Before tank-mixing with other products, ensure that they are compatible. A jar test can test for physical compatibility. But for biological compatibility, technical information from the manufacturer/distributor, or personal experience, is vital.

Do not look to external signs of mycosis as a measure of success, because insects may die long before that happens, or it may never happen. Instead, look for dead or discoloured pests, or the overall reduction in pests after two or three applications.

Think proactive or preventive: detect pests as soon as possible, intervene early in the pest cycle at low to medium pest pressure, and be prepared for subpar performance under high pest pressure or outbreaks. Do not expect quick knock-down. It may take three to seven days before the host stops feeding, laying eggs or dies, so mortality is not immediate.

Select the most appropriate application method and equipment to get complete coverage. As contact insecticides, complete coverage of all above-soil plant surfaces is critical for best control. While secondary contact by walking over the spores does lead to infections, primary contact through spores landing on the insect’s body is generally more efficacious. Apply early or late in the day as UV light will degrade spores.

Lastly, if trying out mycoinsecticides for the first time, consider conducting your own smaller-scale trial rather than changing over spray practices completely. Or, use them as substitutes for a chemical insecticide in your typical rotation. In other words, test on a small scale before going “all in.”

A final message of advice is to reach out to the manufacturer and/or distributor if you need help! As with other microbial and macrobial biocontrols, access to technical guidance will build your confidence to incorporate mycoinsecticides as part of a successful pest management program.

Daniel Peck, PhD, is an entomologist and biological program manager at BioWorks, Inc. He can be reached at dpeck@bioworksinc.com.

Print this page