Features

Crop Culture

Growing Media

Hydroponics, aquaponics, aeroponics and other techniques

A comparison across soilless systems – is one better than the other?

May 20, 2022 By Dr. Mohyuddin Mirza

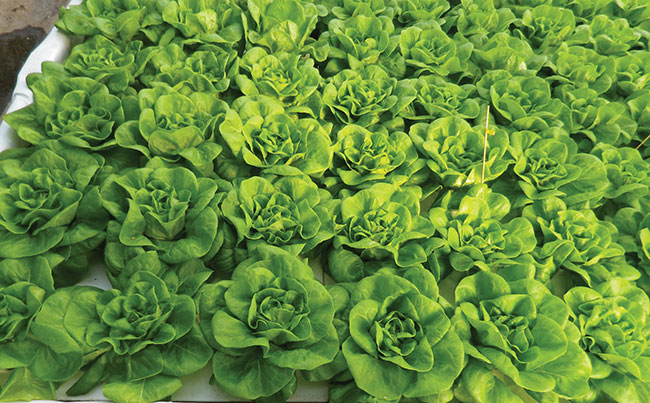

Commercial lettuce production in deep flow, floating hydroponic systems.

ALL PHOTOS courtesy of Mohyuddin Mirza

Commercial lettuce production in deep flow, floating hydroponic systems.

ALL PHOTOS courtesy of Mohyuddin Mirza It was 1980 when I first had to learn about hydroponics, a word that literally means “water works.”

During that time, it became impossible to grow greenhouse vegetables in the soils of Alberta. Root knot nematode affected the production of cucumbers to such an extent that the economic viability of the industry was threatened. There were two commonly used methods to disinfect the soil: steaming and using chemicals like Basamid. Neither of them worked because the nematodes had “learned” to move away around the greenhouse poles or into nooks and corners before moving back to the plants and infecting them all over again.

Our team, located at what was then known as the Alberta Horticultural and Special Crops Research Centre in Brooks, Alta., started researching different growing media and hydroponics methods to cultivate cucumbers, tomatoes and peppers. Between 1980 to 1984, we tested strawbales, peat pillow bags, sawdust and nutrient film techniques (NFT). We designed nutrient delivery methods, held several open houses for growers to view the trials, as well as prepared how-to manuals and publications. By 1984, almost all vegetable growers had switched to soilless cultivation techniques, and the industry bounced back to an economically viable position.

This was also the time when I became aware of the research work done by Dr. Allen Cooper on the nutrient film technique. A group of tomato growers in southern Alberta invested in NFT set-ups and successfully grew tomato crops. Unfortunately, there were many issues which emerged in NFT-grown tomatoes, such as the need for Pythium control and nutrient management in recirculating solutions. Cucumbers did grow very nicely for 100 days, but would then quit due to the development of massive root systems. The root mats were so thick that they started senescing and affecting the top growth of the plants. Pursuit of an NFT hydroponic system was abandoned.

After experimenting with different media, there was a transition period where commercial growers tried the different options. Many growers in Alberta switched over to rockwool, but coir started coming into the picture in the early 2000s and many started using this as the main growing medium instead. Lately, rockwool has been gaining ground again. Growers will keep on changing their growing media based on cost, ease of handling, disposal and other considerations.

Looking at different systems

Hydroponics

Soilless cultivation by hydroponics is the most commonly used technique world wide. That includes cultivation in sand, peat moss, rice hulls, gravel and other locally available growing media. The use of coir has expanded significantly now. There are also variations of the hydroponic system, such as floating Styrofoam panels with plants, nutrient film techniques, deep flow channels and other similar techniques.

Nutrients are delivered via a drip irrigation through injectors, and leached water is drained to waste or recycled. Note that hydroponics is just another method of production and when it first came out, the benefits were often compared to production in soil. The touted benefits of using hydroponics, like less water use, lower disease pressure, and better quality crop – all should be understood in proper context and with relevant comparisons. I recall how growers in Alberta took four years to successfully switch over from soil to hydroponic systems, and only after they had gained a thorough understanding of nutrient delivery and crop management from open house demonstrations and technical manuals.

A tomato crop grown in coir bags must still be well managed in order to produce great yields.

Aquaponics

I had the pleasure of working with Dr. Nick Savidov when he was researching aquaponics systems at the Crop Diversification Centre South in Brooks, Alta. and thus learned about growing fish and plants together.

Simply stated, this system incorporates fish reared in water tanks, and the waste they produce is biofiltered and run through the root zone of the plants. The plants absorb the nutrients they need, the water is returned to the fish tank, and this cycle continues.

This system can keep recirculating such that very little additional nutrients are needed. One may have to add a few nutrients based on the crop’s needs and performance. Fish feed is regularly added as well.

Research shows that, once the microbial population within the aquaponics system has fully developed to change fish waste into plant food, this method can substantially increase crop productivity. Greater crop productivity combined with the additional revenue from fish sales can improve the economics of greenhouse investments in colder climates as well as the financial resilience of greenhouse operators. However, many growers do not want the added burden of marketing fish.

It is my observation that the nutrients involved in aquaponics are far lower than what we supply in hydroponics systems. Because of this, plants have to produce massive root systems to absorb smaller amounts of these nutrients.

Under the Safe Food for Canadians Regulations, aquaponically cultivated products can now be legally labelled as organic if they are certified by an approved certifying body in accordance with the organic aquaculture standard. According to the CFIA, producers are encouraged to provide voluntary information about which standard the product was certified under.

Lettuce in a model aquaponics system with 15 tilapia. In this system, the fish were reared directly in the tank and the water was oxygenated.

Aeroponics

Aeroponics is a type of hydroponic system where water with dissolved nutrients is sprayed at the base of the plants. Proponents claim that the benefit lies in the availability of oxygen right at the root level. The picture shown above is of an A-frame set-up. One can see a massive plumbing system of nozzles used to fertigate the crop. Here, the aeroponically produced lettuce was comparable in yield and quality to those produced in a floating hydroponic system.

greenhouse lettuce. The nozzles actively fertigate the crop.

Is one system better than the other?

Here, I have given a historical perspective on the development of hydroponic systems in Alberta. The primary reason behind this change was that production in soil became impossible due to disease pressure. Soilless cultivation provided producers with an alternative at the time. Even in other parts of the world, one can see where the use of hydroponic systems have allowed for cultivation where it is not possible to do so in soil.

The bottom line is that hydroponic systems have developed bench mark yield data and any new systems now have to achieve comparable or higher yields. On an annual basis for example, regular Long English cucumbers yield over 200 pieces/m2, mini cucumbers yield over 70 kg/m2, tomatoes over 60 kg/m2, and peppers over 30 kg/m2. For leafy vegetables like lettuce, the bench mark yields are around 50 kg/m2 per year.

In the end, be sure to choose a system that best suits your needs, draws from the expertise available to manage the production system, as well as satisfies the market’s demands. There has been a growing focus on sustainability, zero carbon foot print and, of course, cost and benefits.

Mohyuddin Mirza, PhD, is an industry consultant in Alberta. He can be reached at drmirzaconsultants@gmail.com

Print this page