Features

Grower Profiles

Management

People

Greenhouse memoirs: A cultivated love

While it may come as a surprise to many, this grower didn’t always love greenhouse work.

June 22, 2021 By Albert Grimm

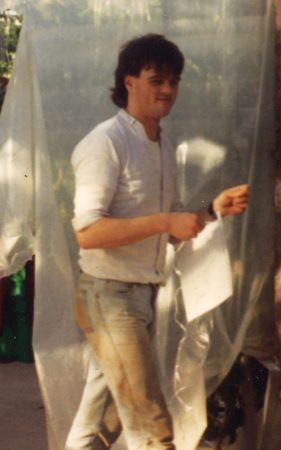

The author working in the remnants of the family greenhouse, circa 1966. Photos courtesy of A. Grimm

The author working in the remnants of the family greenhouse, circa 1966. Photos courtesy of A. Grimm This is my story of 40 years in the greenhouse. It is one of love and hate, a story of times that were difficult, but in the end carried a reward. Before I start, I can honestly say that I have no regrets. Work without difficult challenges quickly turns mind-numbing and monotonous, and I am happy that I was spared such a fate.

I did not always have this perspective. When I came out of high school, I was a beanstalk and a book nerd, void of any form of muscle. Even the German army considered me unfit for compulsory service, because they were afraid that I would not survive base camp. The last thing on my wish list was a career that involved physical work. My real interest was in particle physics, but I would not have turned down an offer to join a professional rock band. However, this was the late 70s. The economy was in the dumps and competition in the music business was fierce. My family was poor, and my stepfather thought that factory work was more honourable and appropriate than university. Student loans, as we know them today, did not exist and this was the end of my aspirations for higher education.

I had to look for something, an opportunity, where I could get paid while being educated, even if just to escape the auspices of my stepfather. My paternal family had owned greenhouses in the past, and this left me with some sentimental attachment to the trade. I found a greenhouse grower who was good enough to hire me as an apprentice for a small retail garden centre and florist shop. We grew everything: cut flowers, tropicals, potted plants, bedding plants, and even market vegetables in the field. Apprenticeship meant that I had to sign a binding, customary contract for two and a half years. I was paid a third of the minimum wage of an average greenhouse worker. I could not be fired, but I also was not allowed to quit without dire consequences. This binding arrangement turned out to be a stroke of luck for me, although it did not sink in until many years later. Within weeks, I had developed a passionate hate for my job and for everything that had to do with greenhouses.

Tomato seedlings proved to require constant muscle work in the greenhouses where the author apprenticed.

Right out of the gate, my apprenticeship master set out with admirable patience to help me develop some muscle. He assigned me to some of the most physically demanding jobs that could be found. In those days, greenhouse work was very different. Growing substrates were prepared from loamy field soil that was first steamed, then mixed by hand with some peat moss, limestone, and slow-release fertilizer. First, we shoveled clumps of heavy soil into the steamer. Then we mixed each batch of potting soil by shovelling it three times from one heap to another. For cut flowers, we turned the greenhouse soil by hand using a spade before we steamed between each crop. Staring down the length of a shovel or spade became a daily part of life.

When we were not shovelling or spading, we were slugging heavy trays of plants. Our growing year started with the forcing of tulips and daffodils. In the fall, the bulbs were planted into heavy wooden crates. They were placed outdoors for vernalization, covered with several inches of fine sand and half a foot of leaf mulch for winter protection. When we were ready to force them for Valentine’s Day, we dug out the crates from beneath the snow and mulch. We carefully scraped the frozen sand from between the sprouting shoots of the bulbs. This had to be done without gloves, so that we could avoid damaging the shoots. We then moved crates by the hundreds, weighing at least 50 pounds each, onto benches in a warm greenhouse. Days of hard, physical labour alternated with equally long days filled with tedious hand-pricking of bedding plant seedlings. Imagine separating tiny Begonia seedlings at an expected rate of 1000 cells per hour with fingers that were still sore from the frost bite of tulip handling. It could break the spirit of even the most passionate of horticulturists.

The equipment used to steam field soil which was mixed with peat to make potting substrate.

Our summers were spent in the fields. We learned the small, but important, difference between various types of hoes. Leeks became my nemesis. The summer heat burned my back while hoeing rows of leeks, and the winter cold froze my fingers when we harvested this vegetable from beneath the snow. There were days when we stood out in the field in oil gear, harvesting pansies with small hand shovels while the driving rain and sleet gradually found their way into our raincoats and down our backs. The quality of those overwintering pansies was incomparably better than anything we find on the market today, but today we would not be able to find anybody who would put up with this type of work.

Once I graduated from the apprenticeship program, I looked for a less challenging work environment and took a job as a grower in the greenhouse of a large, publicly owned mental health hospital. What a difference in work environment. At the end of my first day in the public service, I was already in trouble. My boss had locked me into the greenhouse 15 minutes before the end of the workday, because it was unacceptable to work even a single minute of overtime. All my colleagues were standing in line, ready for the punch clock five minutes before the quitting bell rang. The work was still physical, but everything happened at a more than leisurely pace. Within two weeks, I was bored and disillusioned.

It was not just that my work had changed. I had changed, too. Against all odds, my apprenticeship master had succeeded in teaching me how to work and how to enjoy the sense of accomplishment that comes with work. My new job, however, was ruled by bureaucracy. There was no challenge to overcome. Workdays are very long, if all we do is wait to punch out the clock. I was assigned to help psychologists with work therapy for their patients, and this allowed me to escape the tedium by paying attention and learning about human behaviour. These were to be my first lessons in people skills, but I quickly realized that I was not made for public service.

A high-tech poinsettia greenhouse of the early 1980s.

In 1986, I participated in an exchange program and spent a summer working in Canada. My job brought me to Sydney, Cape Breton, N.S. and since I knew nothing about Canada, I had no expectations for anything other than wild forests, rivers, and waterfalls. It felt like heaven. I worked for a nursery and landscape operation, and this was the most physical job I had ever held: 60 hour weeks, planting trees with a pickaxe and shovel in soil that was too rocky and hard for the Bobcat to break. It was one of the best summers of my life. This time, I quickly shed my lazy flesh and enjoyed the experience of working alongside some of the kindest people on this planet. Much too soon, the first snow arrived by the end of September. The nursery was shuttered for the winter, and I had to return to Germany. My mind, however, was set. I would be back. I worked for some time as a gardener for the Canadian Armed Forces base in Lahr, Germany. Eventually, Canada approved my permanent residency.

I knew that I needed to find a serious job in my new country. The nursery in Cape Breton offered me work for long enough to get started, and by the end of the summer I had bought myself a railway ticket for a job hunt across Canada. I was successful in Montreal, Que., where I was hired on the spot by the executives of SNC Lavalin as a grower for their tomato greenhouse side project in Mirabel. It was the strangest job interview ever.

“Do you have experience with greenhouse tomatoes?”

“Sorry, no.”

“Well, do you have experience with hydroponic vegetables?”

“Sorry, no again.”

“But you have worked in an actual production greenhouse before?”

“Yes, that is my trade.”

“Great. We have nobody with any greenhouse experience. You are hired. You start Monday morning.”

The author working as a tomato grower circa 1989. Photos courtesy of A. Grimm

I was paid minimum wage plus a quarter to manage one hectare of tomatoes and 15 workers. I was happy, but no experience in hydroponic tomato production meant that the results in the greenhouse were a disaster. Within two years, we had lost two tomato crops just days into the first harvest. I started to realize that greenhouse growers don’t get paid to do everything right, but rather to make sure that nothing goes wrong. This was a chance to prove that I was up to the challenge. After many months, my colleagues and I figured out that our irrigation water became contaminated with herbicide runoff after every downpour. We had lost multiple crops, which was bad for the company, but we had solved the puzzle and proved that we knew what we were doing. It was the first time that I had really enjoyed greenhouse work. I realized that I had found passion and gratification in taking on difficult challenges and in conquering seemingly insurmountable obstacles. By the time the owners of this greenhouse had finally decided that farming was not a good fit for their business model, I had recognized that life as a grower was worthwhile after all.

Afterwards, I moved to Southern Ontario and found work with a small but expanding kalanchoe producer. The owner was a tough manager, but I was looking for meaningful challenges and the chemistry between us worked really well. He was brilliant at seeking out business opportunities and brazen enough to take advantage of them. I learned a great deal from him on how to run a company, and I believe that it was the tension between the perspectives of a business-oriented manager and a crop-oriented grower that made this business successful. It allowed us to produce quality that was among the best on the market while maintaining one of the most cost-effective operations in our industry, but it left me with no illusions about my chances for success if I were to own a business.

I had invested an enormous amount of energy and time into my work and I was rewarded with accomplishments that I am very proud of, but years of extreme workload and self-imposed stress had taken their toll. The rapid expansion of the operation meant that I was under constant, severe pressure. The thrill of professional success was such that I had given up on my social life and substituted it with work. Within 10 years, I had successfully completed the 12 classical stages of burnout. I had reached my mid-life crisis. Managing stress and time became paramount when knowledge and hard work, or even sheer bloody-mindedness no longer did the trick.

It was at this time that fate brought me to Jeffery’s Greenhouses, and I crossed paths with several wonderful and powerful mentors who helped me discover an entirely new perspective on achieving professional and personal satisfaction in life. It changed my work and my career. This time, the challenge was no longer to grow plants, but to grow people. Before I could do that, however, I had to learn how to grow myself, which proved to be a rather difficult experience. Today, I know that we cannot help others balance their lives and careers, and we cannot try to make them happier, more effective growers, supervisors, or managers, unless we have personally experienced both sides of life. All of us struggle with our demons, but we must learn how to face them and wrestle them down.

With wife, Stella, who is patiently married to this grower.

What is the point of this long story, you may ask? It was meant to be a retrospective on 40 years in this industry, but what I uncovered extended beyond greenhouse work. When I search for meaning among all these years, I find it in the learning. All of us learn from people who pass knowledge onto us. It should be our passion to then impart this knowledge onto future generations. Learning is a journey without an ultimate destination. Some of us stop to learn, but then we can no longer claim to be teachers, and if we stop teaching, all that we have learned has lost its purpose.

Some years ago, I listened to a presentation by a gerontologist who used a powerful image that deeply resonated with me. The speaker compared human lives to pebbles, which are thrown into the still waters of a pond. The pebbles sink to the bottom and are forgotten, but the ripples on the water’s surface continue moving for a very long time. I hope to leave some ripples behind. For me, this would be a successful life and a successful career. What about you?

Albert Grimm is head grower at Jeffery’s Greenhouses in St. Catharines, Ont. Reach him at albertg@jefferysgreenhouses.com

Print this page