Buying biomass by the tonne means that users could be paying for excess water, not heat.

One of the hidden enemies of an efficient supply chain is a simple compound: water. Because of the importance of this subject, I will take a couple of columns to cover the topic properly.

|

Water occurs primarily within the biomass itself, but in winter, it can also show up as snow and ice clinging to tops and branches or on top of uncovered storage piles of comminuted residues. Moisture content is the single most important quality criterion for forest-origin biomass, yet we rarely manage it. To put it frankly, moisture content is not managed because we either don’t recognize its importance throughout the supply chain or we don’t want to be bothered measuring it. Although attitudes are changing, harvest residues are often taken for granted and not treated as a product from the forest.

The most common scenario today is for feedstock payments to be made on a green tonne basis at the mill gate, thus inciting the supplier to deliver the material as moist as possible to maximize payload. This results in paying for excess water, with a negative energy effect and a less efficient bioenergy system than it should be. On larger-scale operations, delivered biomass is often stored uncovered for months, leading to increases in moisture content or losses in dry matter.

Before addressing the management of residues for the control of moisture, I will introduce why moisture content is important, or more precisely, why low moisture content should be an objective of any biomass supply chain. Because most of the biomass used today is for burning, whether it is for the generation of heat, CHP, or simple (and inefficient) electrical power, we need to understand that water must be “burned off” before the energy value of wood is realized. Another emerging use of forest feedstocks is for pellets. Additional energy for drying needs to be applied to the feedstock to reduce the moisture so that the final product from the dies is less than 10% moisture. The wetter the material, the more heat that is wasted.

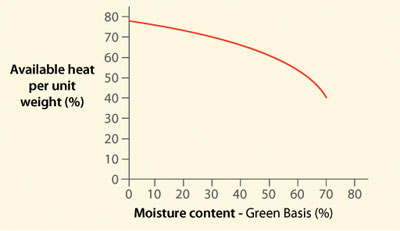

Biomass burners are not all built the same, but they have more-or-less similar burning efficiency curves (Fig. 1). The burning efficiency, expressed as the available heat per unit weight at a given moisture content decreases from a maximum of about 80% at 0% moisture to 40% at 70% moisture content. For example, burning fresh residues at 50% moisture content would result in a burning efficiency of 61%. The heat curve drops slowly until about 30% moisture content, rapidly between 35 and 50%, and then dramatically above 55%.

There is also a common misunderstanding that different types of woody biomass differ in energy content. When expressed on a weight, rather than volume basis, the energy value does not vary greatly between species or parts of a tree and only varies by about 10%, from just less than 19 to 20.5 megajoules/kilogram.

In a simple analogy, you wouldn’t use wet firewood in a wood-burning stove if you want sufficient heat from it. You wouldn’t pay for green firewood the same as you would for dry firewood, and if you do buy it (at a lower price) you would season it before using it the next winter.

Small- and medium-scale boilers require more homogeneous feedstocks with lower moisture content, so there is ongoing attention to feedstock quality. Large modern boilers such as those used in Nordic countries can handle various feedstocks at almost any moisture content, but that does not mean that excessively wet biomass is acceptable. European mill managers recognize the value of low moisture content and pay for biomass on a megawatt-hour (MWh) basis. I am also amazed at how field practitioners in those countries know the “volume” of a roadside pile of harvest residues or stumps in MWh content. They don’t talk about green tonnes. Deliveries are usually monitored for moisture content using systematic sampling, or volume and weight conversions are used when shipments from known providers are relatively stable. Under all approaches, payments for harvest residues are based on energy content, not green weight.

In my next column, I will show an example of the cost implications of delivering wet biomass and discuss some approaches to manage the moisture content of biomass.

Mark Ryans is with FPInnovations’ Feric division and can be reached at mark.ryans@fpinnovations.ca.

Print this page