Aug. 18, 2009 — Biologists have discovered that a

Aug. 18, 2009 — Biologists have discovered that a

fundamental building block in the cells of flowering plants evolved

independently, yet almost identically, on a separate branch of the evolutionary

tree – in an ancient plant group called lycophytes that originated at least 420

million years ago.

|

|

Lead author Jing-Ke |

Aug. 18, 2009 — Biologists have discovered that a

fundamental building block in the cells of flowering plants evolved

independently, yet almost identically, on a separate branch of the evolutionary

tree – in an ancient plant group called lycophytes that originated at least 420

million years ago.

Researchers believe that flowering

plants evolved from gymnosperms, the group that includes conifers, ginkgos and

related plants. This group split from lycophytes hundreds of millions of years

before flowering plants appeared.

|

|

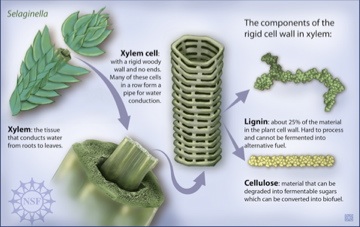

Frond of the lycophyte Selaginella |

The building block, called syringyl

lignin, is a critical part of the plants’ scaffolding and water-transport

systems. It apparently emerged separately in the two plant groups, much like

flight arose separately in both bats and birds.

Purdue University researcher Clint

Chapple and graduate students Jing-Ke Weng and Jake Stout, along with

post-doctoral research associate Xu Li, conducted the study with the support of

the National Science Foundation, publishing their findings in the May 20, 2008,

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“We’re excited about this work not

“We’re excited about this work not

only because it may provide another tool with which we can manipulate lignin

deposition in plants used for biofuel production, but because it demonstrates

that basic research on plants not used in agriculture can provide important

fundamental findings that are of practical benefit,” said Chapple.

The plant studied – Selaginella

moellendorffii, an ornamental plant sold

at nurseries as spike moss – came from Purdue colleague Jody Banks. While not a

co-author on the paper, Banks helped kick-start the study of the Selaginella genome with NSF support in 2002, and is now scientific

coordinator for the plant’s genome-sequencing effort conducted by the

Department of Energy Joint Genome Institute in Walnut Creek, California.

“Because Selaginella is a relict of an ancient vascular plant lineage, its

genome sequence will provide the plant community with a resource unlike any

other, as it will allow them to discover the genetic underpinnings of the

evolutionary innovations that allowed plants to thrive on land, including

lignin,” said Banks.

|

|

|

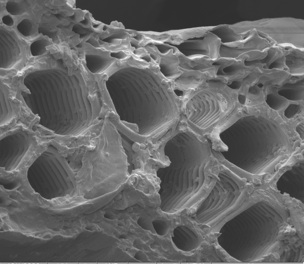

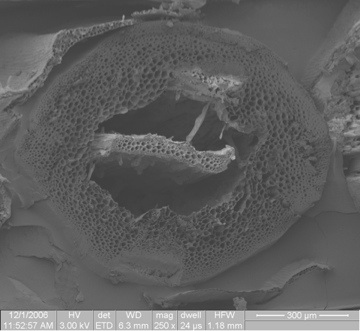

Scanning electron microscope view of |

|

|

Scanning electron microscope view of |

Chapple and his colleagues conducted

the recent study as part of a broader effort to understand the genetics behind

lignin specifically, as the material is an impediment to some biofuel

production methods because of its durability and tight integration into plant

structures.

“Findings from studies such as this really have implications

regarding the potential for designing plants to better make use of cellulose in

cell walls,” said Gerald Berkowitz, a program director for the Physiological

and Structural Systems Cluster at the National Science Foundation and the

program officer overseeing Chapple’s grant. “Different forms of lignin are

present in crop plant cell walls; engineering plants to express specifically

syringyl lignin could allow for easier break down of cellulose. Overcoming this

obstacle is an important next step for advancing second generation biofuel

production.”

The National Science Foundation

(NSF, www.nsf.gov) in the U.S. is an independent federal agency that supports

fundamental research and education across all fields of science and

engineering, with an annual budget of $5.92 billion.

Print this page