Features

Business

Trends

Tech opinion: Blockchain in agriculture

With food recalls and consumer distrust of food origins, can this trust protocol power a new era of smarter food safety?

October 1, 2019 By Shubh Singh

Hippocrates, the Greek physician known as the father of medicine, once said “Let food be thy medicine, and medicine be thy food.” This timeless wisdom encourages consumers to cut back on processed foods and revert to whole food diets rich in fresh fruits and vegetables. But to get to this point, consumers must be able to trust their food.

Consumer demands for ‘clean labels’ extends beyond simply knowing what ingredients go into foods—it is demanding transparency across the entire journey of food from farm to fork. The trouble of trust in our food systems is not limited to consumers, as businesses must also cooperate and establish a trusted chain of buyers and sellers to achieve food safety, efficiency and accountability.

What is Trust Anyway?

Trust can be thought of as a bank account. Each positive transaction is like a deposit that builds consumer confidence, goodwill and loyalty. However, all it takes is one bad experience that serves as a withdrawal, clearing the accounts of all the goodwill that a brand has built with customers, or a business has built with trade partners. Trust is what is broken when a foodborne illness is transmitted from inside a food production, manufacturing or processing facility and into the consumer’s kitchen or fridge. Consumer confidence can change quickly, and holding onto it depends upon the entire supply chain to work in perfect harmony.

Blockchain: A Digital Institution of Trust

Blockchain, or Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT), maintains a record, or a ledger of transactions in a distributed format across buyers and sellers (called ‘nodes’). In other words, there is no central database kept by any one party, enabling the transfer of assets or information between buyers and sellers without going through a third-party intermediary. Without a central authority involved, it is a true peer-to-peer network where information is validated by computers on the network using mathematical algorithms.

Thinking of it as an operating system for transactions, it has the potential to vastly reduce the cost and complexity of doing business. Because of how blockchain is built, transactions are visible and allow for consensus, the origin of each block on the blockchain can be identified, and once created, the blocks cannot be altered. This promotes transparency and trust.

The state of food safety

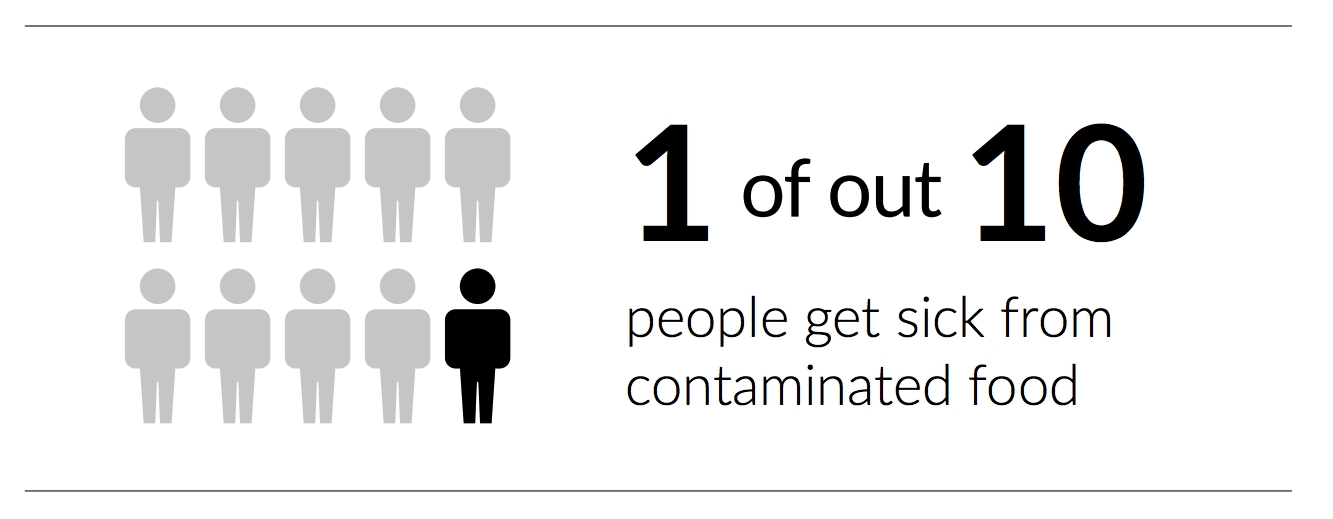

Globally, one out of 10 people get sick from contaminated food and more than 400,000 people die from foodborne illnesses each year (WHO, 2019). Since 2002, food recalls have more than doubled (NY Times, 2016), yet the capabilities of current traceability systems struggle to respond swiftly and with targeted actions to today’s global food supply chain challenges.

While consumer health and safety are the primary concern, it is also important to identify the specific source of contamination along with its distribution and retail routes to market. Understandably, retailers tend to quickly pull product from their shelves when an outbreak occurs, choosing to err on the side of caution, but the economic impact is felt by all growers of that crop. As noted by Peter Patterson, blockchain leader for IBM Canada, blockchain has the potential to not only improve consumer safety but to also substantiate the safety of a grower’s product, which otherwise might be swept up in a mass recall.

How did we get to now?

As a society we have begun to demand more and more when it comes to our food. We want the freshest foods, available year-round, at reasonable prices, delivered to our doorstep. This growing desire for speed, access, and convenience has caused supply chains to morph from once serving up food from “around the corner” to “around the world,” making them increasingly complex, interconnected, and dependent upon several intermediaries—all of which have made it more difficult to track and trace food back to their origins. A network with real traceability is imperative for consumers to trust what they are buying.

In times of recalls, retailers must be able to pull any food with the potential to carry bacteria and pathogens that can cause foodborne illnesses. A study by Ohio State University estimated that the annual cost of food-borne illnesses tops $55.5 billion in the United States alone. Coupled with the fact that food fraud is estimated to cost the global food trade around $40 billion annually, there is a need for improvement in food safety standards and controls.

Where do we go from here?

Some point to regulatory bodies like the FDA and CFIA who set the standards on what the term “safe food” can mean and what it should mean. The FDA has acknowledged the growing concerns surrounding food safety and the fact that, despite our systems being “pretty safe,” incidents such as the E. coli outbreak in November of 2018 still occur.

The crux of the problem is that many players in the food system utilize a largely paper-based system of taking one step back to identify the source and one step forward to identify where the food has gone. These systems are a far cry from what is possible.

With the proliferation of mobile devices, cloud computing, sensors, and DLT technology, a permanent and tamperproof blockchain can enhance traceability by providing a single source of truth in a fruit’s journey to determine whether it is deemed safe to consume and identify who is at risk across the supply chain. As such, The FDA has committed to exploring artificial intelligence, machine learning, the internet of things and DLT to create more digital, traceable and safer systems.

- What is blockchain?

Blockchains are shared databases or ledgers of information about transactions and events.

A blockchain consists of blocks, and like individual pages of a ledger, each block contains the data or transaction, what’s known as its hash value (a unique cryptographic value of characters and numbers assigned by a computational algorithm), the hash of the previous block to link the blocks in order, and a timestamp. - How does blockchain apply to agriculture?

Some suggest that a blockchain is like a Google document where multiple authors can contribute. Blockchain is a bit more complex than that, but its inherent transparency and security, among other unique characteristics, make it an attractive technology for tracing food from production to delivery, enabling tagging, storing and tracking anything of value.

Digitization of Food Systems

In Canada, the CFIA is undergoing a two-year initiative involving collaborations with industry to test practical applications of DLT in information sharing, supply chain management and traceability.

Brian Kowaluk, a member of CFIA’s Data Analytics and Modelling team, says “The larger trend here is the digitization of the food system. In Canada, we have a strong food safety system and traceability requirements, but we are always trying to enhance that system by working with all players—industry, governments and consumers—to safeguard the food we eat. Our goal is to maintain food safety, thus we are exploring ways [in which] technologies such as blockchain can be used to link systems, reduce administrative burden, and minimize the cost of compliance. There are many promising benefits of instituting blockchain technology beyond food safety which may be a bigger driver to implement these systems.”

A Common Language

“Blockchain is not a specific software, it is a methodology for sharing data between trading partners,” says Ed Treacy, vice-president of supply chain efficiencies for the Produce Marketing Association (PMA) and an official advisor of IBM’s Food Trust. Treacy leads the PMA’s Blockchain Task Force, a group of industry practitioners that examines different ways in which the technology is being used across different firms.

“It’s a hot topic, kind of like the dot.com buzz of the 90’s. Many players are building and testing blockchains as we speak, but what is important is that we as an industry develop a common language for communication.”

GS1 (Global Standards One), the not-for-profit organization that develops and maintains global business communications standards such as the GTIN barcode, has also been working to educate and advocate to advance discussions around blockchain data standardization.

Putting Blockchain to use

IBM’s Food Trust is one of the first in-production solutions using blockchain. Since 2016, Walmart and IBM have worked together to envision a fully transparent food system. In 2018, Walmart made waves when it notified its leafy greens suppliers that their products must be on the blockchain within one year’s time.

The IBM Food Trust provides authorized users with immediate access to food supply chain data, from farm to store and ultimately the consumer. The complete history and current location of any individual food item, as well as accompanying information such as certifications, test data and temperature data, are readily available in seconds once uploaded onto the blockchain.

Onboarding onto IBM Food Trust requires uploading data about your product’s lifecycle, including information on harvesting, manufacturing and transportation, but there is no need to have an intimate understanding of blockchain.

The platform collects data already in use and with industry standards. By simplifying the requirements for participation, IBM expects adoption to grow organically ahead of any possible regulatory or retail mandate. By sharing supply chain data on a permissioned basis, IBM also expects several commercial benefits to help drive adoption, such as lowered costs of administration, higher consumer confidence, and better inventory

management.

Prepare for a Revolution

The process of transforming produce into data on a blockchain does not happen on its own. Currently, it requires human intervention for data entry. However, integrated automation solutions for packaging and labels have become the vehicle with which products are digitized, tagged, stored and tracked along the supply chain. Today this is happening via Price Look Up (PLU) labels using the GS1 GTIN Standard, but soon, fruit stickers using QR Data Matrix will be the bridge connecting physical products and digital identities. Packaging and labels will become increasingly important in verifying the integrity and authenticity of a given product.

Blockchain is expected to do for transactions what the internet did for information. Market movers such as Walmart, with the help of the IBM Food Trust, have embraced the technology and made blockchain part of their supplier network.

Deployed correctly, blockchain technology has the potential to enhance efficiency, transparency and traceability across the food system. Members of the industry are working to further investigate the possibilities, understand how it can support supply chain imperatives, and address the technological, regulatory, and operational implications of adopting an entirely new paradigm.

Shubh Singh leads business development at Accu-Label International, and is a member of the PMA’s Blockchain Task Force, Product Identification Group, and Sustainability Committee. Shubhs@accu-label.com

Print this page