Features

A place for pesticides

There are times when releasing beneficial insects isn’t the most effective or economical course of action.

January 30, 2023 By Mike Short and Sarah Jandricic

FIGURE 1

Applications of pesticides are sometimes your best bet in a floriculture IPM

program. Always check the label for any instructions on how to best apply the

product (e.g. “spray to glisten” for some products; “spray to runoff” for others).

FIGURE 1

Applications of pesticides are sometimes your best bet in a floriculture IPM

program. Always check the label for any instructions on how to best apply the

product (e.g. “spray to glisten” for some products; “spray to runoff” for others). Born out of a need to battle insecticide-resistant pests with relatively few chemical options, the greenhouse floriculture industry in Canada has earned its place as a world leader in the use of biological control over the past 30 years. Most of the time, high-quality, residue-free crops can be produced exclusively with this pest management tactic. Sometimes, however, there are times where releasing beneficial insects isn’t the most effective or economical course of action.

Focusing on biocontrol as the main tool in the IPM toolbox means opportunities to reduce your bottom line with pesticides for specific pest issues can be missed. More serious situations can also arise when growers are hesitant to intervene early in a pest management issue with chemical controls, over fears they will irreparably damage their biocontrol program.

Although some level of apprehension before digging into the pesticide cabinet is absolutely warranted, both pesticides and biocontrol have a place in successful crop production, if care is used. In this article, we’ll guide you through some scenarios where we see a place for pesticides in greenhouse ornamental crops, which pesticides to pick, and how to use them most effectively.

A time for pesticides

Although the days of “calendar spraying” are long behind us, you’ll still want to take note of when certain pests predictably become a problem and have a management plan in place. This plan should include biocontrol agents, mechanical controls (e.g. mass trapping), sanitation (e.g. rouging plants infested with more sedentary pests, like Lewis mite) as well as potential pesticides in case these tactics aren’t effective.

A time of year we know can be a potential issue is hot, summer months. When outdoor crops are harvested, or when weed hosts die off, large numbers of adult western flower thrips (WFT) or onion thrips can fly into greenhouse crops through vents and other openings and cause significant damage quickly. Since predatory mites are not able to kill adult thrips, this is the time to aggressively add in weekly sprays of Beauveria-containing microbial pesticides (Fig. 1). This can drastically reduce adult thrips populations. Some growers are able to manage thrips populations in summer crops, such as garden mums, using Beauveria and mass-trapping alone, with significant cost savings.

Once the days become darker, shorter and colder, certain biocontrol agents can also become less effective. This is fairly common knowledge when it comes to Orius and parasitoids for aphids and whitefly, but the predatory mite N. cucumeris has recently been shown to establish less in winter as well 1. One strategy to combat this is to get good establishment of your natural enemies in fall and go into these drearier days with low pest levels that can be ridden out. If this isn’t achievable, then sometimes repeated pesticides applications can get you through this period. Biocontrol agents can be re-introduced when climate conditions are more favourable (generally in the first week of March), as long as you use chemical products with short-to-moderate residuals (see Table 1).

When pests are on the rise

Probably the best time to consider incorporating pesticides into your IPM program is when monitoring indicates pest levels are rising dramatically. This could indicate a sudden influx of pests (from outside or from incoming plant material), or that your biocontrol program is unable to keep up for

some reason.

A good example of this is with thrips pests other than western flower thrips (WFT). Growers are understandably reluctant to turn to pesticides because of our experience with WFT and its widespread pesticide resistance. However, typical mite-based biocontrol programs designed for WFT aren’t entirely effective for thrips pests like onion thrips (Thrips tabaci) 2, tropical tabaco thrips (Thrips parvispinus) 3 and Echinothrips (Echinothrips americanus) 4. Relying on predatory mites only in these cases can result in high thrips population and significant crop damage. Luckily, all three of these thrips species are more susceptible to pesticides than WFT. Applications of products such as Success (spinosad), Kontos (spirotetramat), Ference (cyantraniliprole) and Beleaf (flonicamid) likely won’t cure your problem entirely but can knock back the problem long and hard enough for you to get out of a jam. As these products have varying ranges of efficacy on these thrips species, they may be best used in combination. All of these chemicals are somewhat compatible with natural enemies (see Table 1), so you can get back to implementing biocontrol in a few weeks, when any residual effects from the pesticide are likely to have passed. Rotating introductions of natural enemies with pesticides also lengthens the time needed between pesticide applications, helping to avoid resistance.

Problem areas

When considering the use of pesticides, the location of the pest problem can also play a factor. In years past, a pest found in one corner of the greenhouses warranted blanket pesticide applications across the whole crop. Now, the dangers of pesticide resistance and derailing biocontrol programs is too high for this type of application, without careful thought. But when applied as spot-spray, or in more self-contained areas, many pesticides can more easily fit into biologically-based IPM programs.

A good example of a problem area where pests pop up year after year is outbreaks of spider mites along the south walls of greenhouses. We often see consistent “hotspots” here, where temperatures may be higher at certain times in the season. Spider mite outbreaks can also occur along the greenhouse walls when weeds are killed off around the perimeter of the greenhouse. Interior weed control and a spot spray of a miticide with a shorter residual in this area of the crop may be the most effective and timely method for impeding further problems. The key to knowing when and where these hotspots might occur is long-term scouting records. Referring to past years notes and pest counts, growers can identify pest patterns and trends to guide their pest management decisions seasonally.

Another common problem that often occurs regularly is in short-term crops. It is common for some growers to broker a certain crop to fill a sales need or utilize available space while partnering with another greenhouse. Often, these products arrive with a pest already present. Time constraints may not allow biological control to be the most effective control measure. Or, the pest may not have an effective natural enemy that works quick enough. For instance, mealybug that arrive on tropical house plants. In this case, the best course of action is to place the short-term crop in a smaller zone by itself (if possible) where a pesticide can be applied without affecting other zones that may have established biological control. Depending on the chemical used, toxicity could persist, so biocontrol may have to be delayed on any follow-up crops in that zone.

Choosing the right product

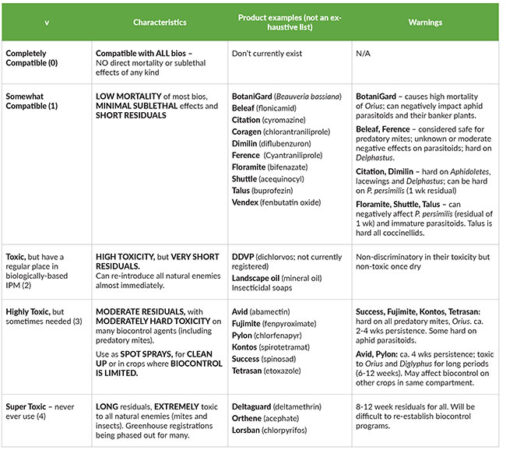

The key to successfully integrate pesticides into your IPM program is understanding both the direct toxicity of the product on your biocontrol agents (mortality rate) and the time the product is still present in the plant, or on leaf surfaces, and remains toxic (residual toxicity time).

Most of the major biocontrol suppliers give compatibility ratings from 1-4 for pesticides, based on guidelines from the International Organization of Biological Control. Products rated a “1” have studies which indicate they cause anywhere from 0-25% direct mortality of particular biocontrol agents. These are considered “compatible” in the industry. Products rated 2-4 cause 25-100% mortality and are considered “moderately soft” (2) to “hard” (4) on biocontrol agents and are often not recommended for use in an IPM program involving natural enemies.

These ratings offer a quick and easy guideline and will be incorporated into OMAFRA’s new pesticide reference tool that will be launched for greenhouse crops in 2023 (Crop Protection Hub, cropprotectionhub.omafra.gov.on.ca). However, as with any quick reference tool, these simple compatibility ratings don’t necessarily tell the whole story.

With a compatibility rating of 2-3 (depending on the insect), soaps and oils are actually some of our best chemical tools in an IPM program that relies mostly on biocontrol. Despite being non-discriminately toxic against all natural enemies (insects and mites), they have a very short residual time. This means biocontrol agents can be re-released once the product is dry or will continue emerging out of sachets already in the crop.

Even more toxic chemicals have their place. In crops where biocontrol is limited (for example, those that use predatory mites only), moderately toxic products can be used as spot spray or to knock back a pest outbreak, as long as they also have moderately short residual times for the natural enemies in use (see Table 1 for product examples). In practice, we see some producers who have success with a single application of a product like Avid (abamectin) to get on top of thrips with one shot. They are then able to re-introduce predatory mites in sachets after a few weeks, as the residual for this product is only two weeks. To be extra cautious, some growers add 50% to the residual time before re-introducing (i.e. giving Avid three weeks, instead of two).

Conversely, products rated a “1” should not be seen as having zero ramifications on biologically-based IPM programs. By applying these products, you may be reducing your population of a biocontrol agent by 25% with each spray. With several consecutive sprays, this could negate your introductions entirely.

Additionally, the complete ramifications of a product may not be entirely captured in current compatibility databases. An example of this is Beauveria-based products. Although consistently rated a “1” against all natural enemies, repeated applications are known to kill both Aphidius colemani and Orius insidiosus at high rates in a greenhouse setting5. Similarly, compatibility rankings don’t often take into account sublethal effects of a pesticide – negative impacts on things like natural enemy reproduction, searching behaviour or lifespan. Ultimately, this means there is no product currently on the market that can be considered completely compatible.

Further, there are many products where side effects are unknown – especially new products, like Ferrence (cyantraniliprole) and Ventigra (afidopyropen), where the data just hasn’t been generated yet. The lack of a negative compatibility rating should never be seen as permission to spray. Instead, test patches should be done in the crop, with monitoring of presence and reproduction of biocontrol agents in that area.

FIGURE 3

An example of using water-sensitive paper in a poinsettia spray trial. Here you can see how the leaves blocked the spray from reaching certain points of the plant (yellow areas). Blue areas indicate good spray coverage.

How the spray is applied can be crucial

As growers know well, the floriculture crops we grow can vary dramatically in crop architecture and canopy density, across plant types and depending on their stage of growth (Fig. 2). In a perfect world, we would have specific sprayers designed for each crop to achieve the best possible canopy penetration and application efficiency.

Because this would not be economically feasible, most growers use a single hydraulic sprayer, which utilizes high volumes of water and pressure to apply insecticides and fungicides to all crops. These sprayers can be effective when crops are young and spaced out, but once the canopy has closed, getting product where it needs to be (generally on the undersides of leaves within the plant canopy) can be incredibly difficult. Where possible, we’ve found the best way to get the best control of most pests (either insect or disease) is through drench applications of systemic products.

For products that are contact or translaminar only, and cannot be drenched, correct choice of machine, nozzle or pressure can make the difference between good and poor coverage. For instance, to help biopesticides like Beauveria work more effectively for thrips suppression, they should be applied via hydraulic sprayer at higher pressures to create more of a mist, or through a Low Volume Mister (LVM) when weather is humid. Compared to conventional hydraulic sprayers, foggers or misters produce smaller (and more numerous) water droplets, which are suspended in the air for longer. This allows lateral air movement in the greenhouse to carry Beauveria spores held in the droplets into the plant canopy, instead of just settling on upward-facing surfaces. For information on using LVMs in greenhouses, check out OMAFRA’s “Sprayers 101” website (www.sprayers101.com) and search for “foggers.”

As a final note on contact insecticides, you should always make sure to place water sensitive paper (Fig. 3) within the crop (in target or hard to reach areas) when spraying these products to determine if you’re actually getting the product where it needs to be. If you’re new to using this tool for assessing pesticide coverage, you can read about it in the three-part series, “Assessing Water Sensitive Paper,” on sprayers101.com.

Table 1

Revised pesticide compatibility rankings on natural enemies. Developed by OMAFRA staff.

How do I know if my pesticides are working?

As a final note on pesticide use, it’s critical that growers compare pest numbers before and after a pesticide application to determine if the spray was effective. Plant taps and card counts are necessary to help with an informed decision on whether further action is needed. Take note of the predominate life stage of the pest (i.e. larval thrips versus adults) to determine the correct pesticide product to use and whether that life stage continues to dominate after the spray. When done correctly, only one spray may suffice (for thrips larvae) or a series of weekly sprays may be needed for a knockdown (thrips adults). The time of the year and levels of pest pressure will determine the urgency and frequency of the sprays and whether your biocontrol can take over the job when done with the sprays.

If your spray application did not have the desired control, it may not necessarily be the fault of the chemical. Check your water pH (most need a range of 6.5-7.5 to be effective), or maybe your nozzle is becoming worn out. Doublecheck the dilution rate as stated on the chemical label. In some cases, more than one application is needed, so don’t despair if the first one was not as effective as hoped. In other cases, products may take a while to translocate to growing points (as we often see with Beleaf, which can take up to two weeks), so patience may be in order.

When more than one pest is present in your crop, it is important to note that when applying a chemical against the targeted pest, it may have a negative effect against the secondary pest. Many insecticides can also affect predatory mites (e.g. Success, Intercept), while miticides can also affect certain insect biocontrol agents (e.g. Fujimite, Tetrasan). An example of this is when abamectin (Avid) is used for mites. It will repel adult thrips away from the area, only to return with a vengeance when the chemical has dissipated. Another well-known negative interaction is when imidacloprid (Intercept) is applied for aphids. Here, spider mites will be aggravated to reproduce causing more of a problem immediately after the spray. Knowing about these interactions can help the grower make an informed decision regarding their overall plan of attack.

The take home message

Overall, to produce crops both sustainably and economically, any one pest management tactic shouldn’t be considered the “end all and be all” solution for all crops and pests. Both bios and pesticides can work in synergy – with careful planning. Being able to switch tracks and to stay dynamic in your pest control solutions is often the key for tricky situations. The more tools a grower has, the more proactive and long-term pest solutions can be realized in their facility. These tools can include both pesticides and biological control.

References:

- Roselyne M Labbé, Dana Gagnier, Les Shipp. 2019. Comparison of Transeius montdorensis (Acari: Phytoseiidae) to Other Phytoseiid Mites for the Short-Season Suppression of Western Flower Thrips, Frankliniella occidentalis (Thysanoptera: Thripidae), Environ. Entomol. 48 (2):335-342, https://doi.org/10.1093/ee/nvz017

- Summerfield, A., Buitenhuis, R., Jandricic, S. and Scott-Dupree, C. 2022. Pesticides for onion thrips: efficacy and compatibility with biocontrol. Poster presentation, 2022 Canadian Greenhouse Conference. At: Niagara Falls, Ontario. Access at: https://www.canadiangreenhouseconference.com/attendee-information/research-poster-session

- https://www.biobestgroup.com/en/news/pepper-growers-should-remain-vigilant-for-new-thrips-threat

- Opit, G.P., Peterson, B., Gillespie, G and Costello, R.A. 1997. The life cycle and management of Echonothrips amiericanus (Thysanoptera:Thripidae). J. Entomol. Soc. Brit. Columbia 94, 3-6.

- Ludwig, S.W.; Oetting, R.D. 2001. Susceptibility of natural enemies to infection by Beauveria bassiana

and impact of insecticides on Ipheseius degenerans Acari: Phytoseiidae. J. Agric. Urban Entomol. 18: 169–178.

Dr. Sarah Jandricic is the Greenhouse Floriculture IPM Specialist for OMAFRA since 2015 and has been working in greenhouse floriculture entomology for over 20 years. Mike Short (M.Sc.) is owner of Eco Habitat Agri-Services and Greenhouse IPM instructor at Niagara College. He has been providing IPM consulting services for greenhouse crops

for over 25 years.

Print this page