Features

Biocontrols

Inputs

Boosting bankers

September 23, 2014 By Drs. Sarah Jandricic and Steve Frank NCSU

By now, most growers have heard of “banker plants” and know that they can be a useful tool in the greenhouse.

By now, most growers have heard of “banker plants” and know that they can be a useful tool in the greenhouse.

|

|

| Banker plants for Aphidius colemani in action in a Begonia crop in Ontario. Photo Courtesy Dr. Steven Frank, Ncsu |

Banker plants are open rearing systems for parasitoids and predators that work by providing them with alternative sources of food.

A number of different banker plants systems are already used in greenhouses.

For example, non-pest aphids feeding on non-crop plants are used to rear Aphidius wasps for aphid control (pictured).

A whitefly species that feeds exclusively on papaya plants are hosts and prey for Encarsia and Delphastus species that attack silverleaf whitefly.

Castor bean plants produce pollen to support Amblyseius swirskii when preying on Western flower thrips.

Banker plants like these have multiple benefits, such as helping natural enemies make a home in your greenhouse, promoting their reproduction, and providing a steady-stream of “fresher,” better pest killers. These benefits help increase the effectiveness, and decrease costs, of biological control agents.

But what IPM practitioners and researchers still don’t know is the best way to use banker plants. What’s the optimal spacing in the greenhouse? What is the best species of plant to use as a banker plant? Does plant cultivar make a difference?

SUPPORTED BY AN AMERICAN FLORAL ENDOWMENT GRANT

These are some of the questions the lab of Dr. Steven Frank (North Carolina State University) was interested in asking and answering as part of an American Floral Endowment grant.

|

|

| Aphidius colemani. Photo courtesy Adam Dale, Graduate Student, Ncsu

|

Our research focused on banker plants for the aphid parasitoid Aphidius colemani (pictured). Aphidius colemaniare parasitoids that control green peach aphid and melon aphid.

The most common banker plant system for this natural enemy includes: 1) a cereal plant, 2) a non-pest aphid species called bird cherry-oat aphid that feeds only on cereals, and 3) the wasp, which uses the bird cherry-oat aphid as an alternative host when it’s not busy killing pest aphids.

Researchers and growers have used many types of cereals in this system before, including oats, corn, rye, wheat, barley, millet, and wild grasses. But no one has compared these head-to-head to determine which produces the most and the best wasps.

We looked at four of the most common grains used – barley, oats, rye and wheat – to see how they affected both the banker plant aphids and the wasps they produce. In “sciency”-terms, we call the ability of plants to negatively or positively

affect herbivores and their natural enemies “bottom-up effects.”

Bottom up-effects are a fairly common occurrence in nature, so it stands to reason that they could have a significant impact on the performance of banker plants in our greenhouses. Since we also wanted to investigate at what level plant effects start to matter, we looked at three cultivars within each of the four grain species.

How exactly did we figure out if plants had good or bad effects on cereal aphids, you ask? Well … let’s just say it involved one undergraduate student named Adam, and a LOT of staring at aphids several times a day to check for survival, growth and reproduction. (Don’t worry – Adam is now a graduate student in our lab, so all his eye-strain paid off! It was sort of like one big, blurry interview process).

HOW DID OATS MEASURE UP FOR BIRD CHERRY-OAT APHID?

What Adam found was that, despite their name, oats were not, in fact, the best food plant for bird cherry-oat aphid. When our cereal aphids were fed this plant, more of them died than on any other plant (38 per cent of the population died, compared to just 14 per cent on the other grain species).

Those that survived had the fewest babies, and aphid colonies reared on oats had the smallest rate of population growth. After two weeks in the greenhouse, oat plants produced 30-60 per cent fewer aphids than barley, rye or wheat. This suggests that somehow oat plants are not providing enough nutrition to aphids for them to grow properly.

Wheat, on the other hand, seems like a very good food source for bird cherry-oat aphids. Wheat plants had the highest surviving number of aphids, and those aphids consistently produced the most babies.

Barley also seemed to be a good host plant, since young aphids feeding on this plant took less time to develop into adults.

Overall, wheat and barley banker plants could support the highest number of bird cherry-oat aphids, producing significantly more aphids per plant than rye or oat.

“Well that’s nice,” some of you might be thinking, “But the idea behind banker plants is to produce wasps, not aphids!” And you would be right. But what we ultimately discovered is that unhealthy aphid populations don’t make especially good hosts for Aphidius.

You see, when we watched individual wasps in the lab for their ability to parasitize and produce offspring in aphids fed one of our four grain species, we noticed a disturbing trend. The Aphidius seemed willing to attack and lay eggs inside oat-fed aphids.

But then…nothing. Oftentimes no wasp would emerge from the aphid mummy. In fact, wasps only successfully emerged from parasitized aphids on oat about half the time.

This trend also held up in the greenhouse. After inoculating banker plants with several adult female Aphidius and letting them parasitize aphids, we collected the mummies from each plant. Not only did we find the fewest number of mummies on oat plants, but again, the emergence rate from these was only about 50 per cent.

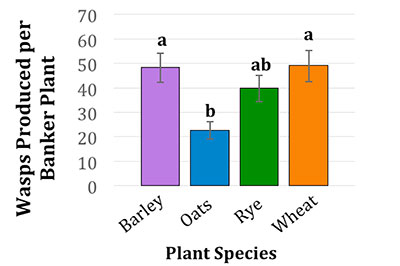

Ultimately, the low abundance of aphids on oat and their poor quality as hosts resulted a measly 22 wasps produced per pot (Fig. 1). This was 54 per cent fewer than when we used wheat, showing that bottom-up effects of plants have a very real effect on banker plant systems.

|

|

| Figure 1. Average number of Aphidius colemani offspring produced per plant from just 2 female A. colemani, depending on the plant species used. All plants supported populations of bird cherry-oat aphid as the host for A. colemani. Different letters indicate statistical differences between averages.

|

STRANGE EFFECTS WHEN USING RYE PLANT

We also saw some strange effects using rye, suggesting this plant, too, is less nutritious for bird cherry-oat aphid and its parasitoid.

On one hand, we had almost as many wasps produced on rye as on wheat plants. On the other (less good) hand, only 26 per cent of these were female. For all other plant species, at least 50 per cent of the wasp offspring were female.

Given that it’s the female wasps that do the actual pest aphid killing, rye doesn’t seem like the best choice for a banker plant either.

So, what does this all boil down to? For those growers interested in producing their own Aphidius banker plants in the greenhouse, we recommend that they choose wheat or barley as their cereal species to ensure the healthiest bird cherry-oat aphids, and the most wasps.

As for the cultivars we tested, the good news is that cultivar didn’t seem to have any effect on how effective a particular plant species was. In other words, one wheat plant seemed as good as another, so growers can use whatever cultivar they find easiest to get their hands on.

As always, though, the effectiveness of banker plants is only as good as their care. Banker plants need to be watered and fertilized regularly, checked to make sure they are still supporting good-sized populations of un-parasitized aphids, and should be replaced every four weeks to ensure that they don’t “crash,” leaving Aphidius without food. With a little tender-loving care, and the right selection of plant species, anyone can have a greenhouse full of little aphid-murdering machines.

Doesn’t that sound like fun? It sure does to me.

Steve Frank is an assistant professor at NCSU. Sarah Jandricic is a post-doctoral entomologist at NCSU.

Print this page